As Malaysia’s bumiputra policy turns 50, citizens debate impact of affirmative action

- The

New Economic Policy is attracting mixed responses about its impact

since Malaysia introduced it in 1971 to enrich the lives of ethnic

Malays and native groups

- But

five decades on, economic inequality has only deepened, leading even

bumiputra beneficiaries to question a policy that experts say is in dire

need of reforms

Firdaus Jesfrydi, 26, has a profile that makes him a perfect match for Malaysia’s majority affirmative action policy.

The ethnic Malay grew up in a home in Sarawak with an annual household income of some 4,800 ringgit (US$1,200), and in 2013 won a preferred spot in a pre-university programme – based on his race – that subsequently allowed him to gain entry into Universiti Malaysia Sarawak to read engineering.

Without the state’s support, Firdaus would not have been able to see the inside of a tertiary institution and improve his prospects.

But on campus, he soon discovered that not everyone who benefited from the New Economic Policy, often called the “bumiputra” (sons of the soil) policy, came from the same background.

Many of his peers were well-off Malays enjoying the same preferential treatment as he was. Others had clearly fallen short of qualifying for university entry but still managed to gain admission despite their subpar grades, thanks to the NEP or their connections.

In contrast, Firdaus said some of his friends who came from ethnic minority backgrounds struggled to get university placements even though they had aced their secondary school exams.

“Affirmative action was meant to reduce inequality, but since it was rigged to favour rich bumis, it did not solve the problems,” said Firdaus, now an engineer.

How NEP came to be

Launched in 1971 by former prime minister Abdul Razak Hussein’s government, the NEP was designed to help eradicate extreme poverty by providing institutionalised advantages to the Malay population and other aboriginal groups, who make up 70 per cent of Malaysia’s 33 million people.

The policy was triggered by tensions between the majority population and the much smaller but wealthier ethnic Chinese community, which culminated in deadly riots in 1969, and Abdul Razak pinned hopes that greater economic equity would help bring about lasting social harmony.

Fifty years on, the NEP has come to represent a political sacred cow. Even the harshest critics of the bumiputra policy have a hard time imagining a realistic alternative to what is now a centrepiece of the country’s governance model.

On occasion, such as during the ongoing budget debates, the policy becomes a political football, although the canny power brokers in parliament know better than to suggest any drastic changes.

At the same time, the programme’s flaws run deep and are so glaring that almost every citizen, both beneficiaries as well as those outside its largesse, have tales of frustration to tell.

A deluge of stories have emerged in recent months amid a national debate during the NEP’s 50th anniversary.

Among Malaysia’s ethnic minority groups, many have accounts that match those of 26-year-old Lishana from Sabah.

Unlike Firdaus, Lishana was destined to face the short end of the stick by virtue of her ethnicity. While she achieved a commendable cumulative pre-university grade point average of 3.14 out of 4.0 to read international financial economics at the University Malaysia Sabah, she discovered some of her bumiputra peers had gained placements with scores that were under 2.0.

Some of these classmates enjoyed free tuition, while Lishana had to obtain a loan to fund her studies. “How frustrating is that?” said the copywriter, who wanted to be known by a pseudonym.

A ‘never-ending’ policy?

The track records of leaders across Malaysia’s political divide offer little indication that even piecemeal easing of the affirmative action programme is a priority.

In fact, successive prime ministers, including the elder statesman Mahathir Mohamad – who held the top political job twice – sought to strengthen the NEP rather than to unwind it.

In September, the newly appointed prime minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob, an ardent Malay nationalist, offered further debate fodder when he declared that corporate equity held by bumiputras could only be disposed of to other bumiputra entities.

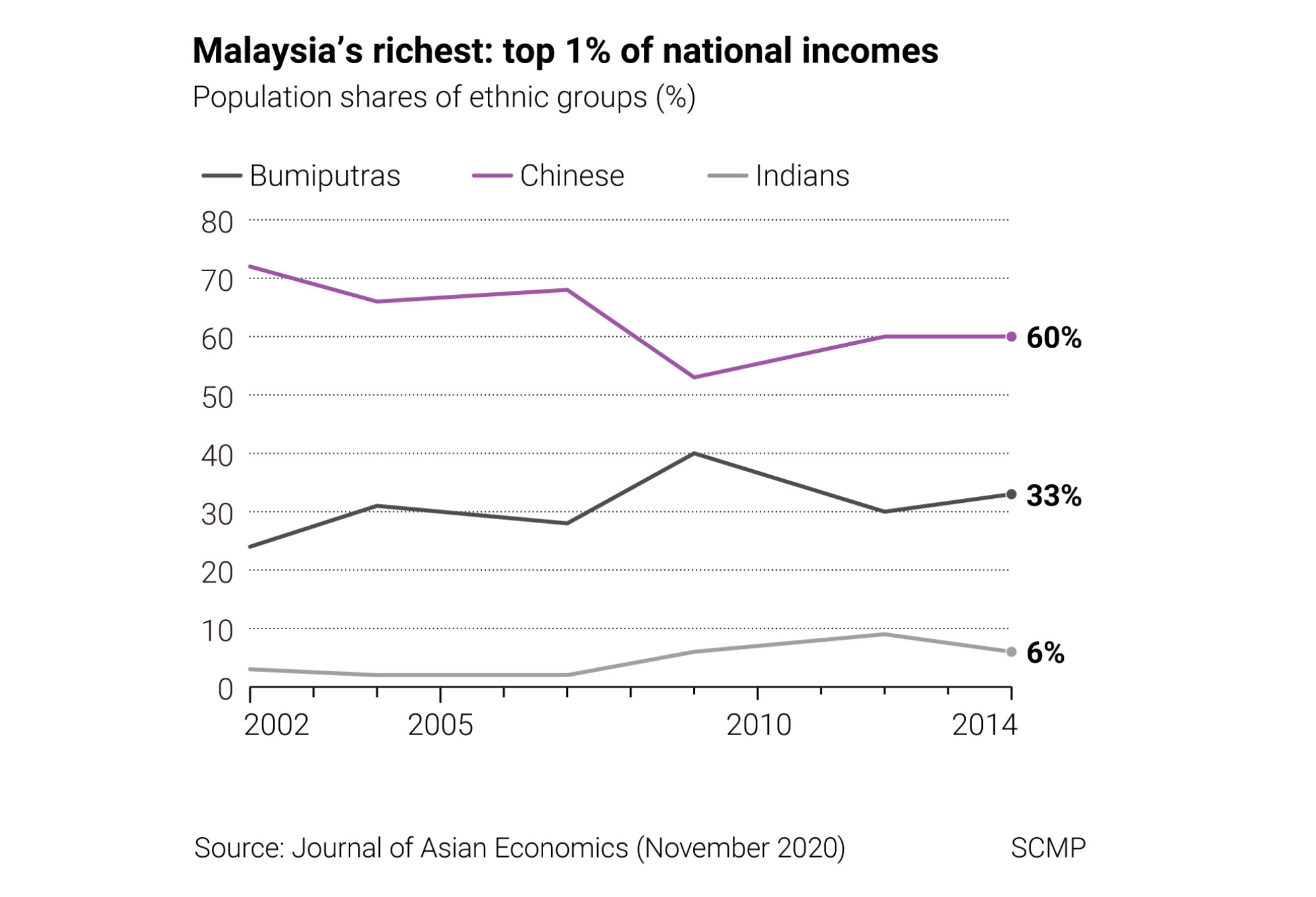

The architects of the NEP had envisioned bumiputras would control 30 per cent of all corporate equity by 1990, from 2.7 per cent when it was implemented.

At present, however, bumiputras control 17.2 per cent of corporate equity, compared with the 25.5 per cent in the hands of those from minority groups, and the 45.5 per cent by foreign nationals.

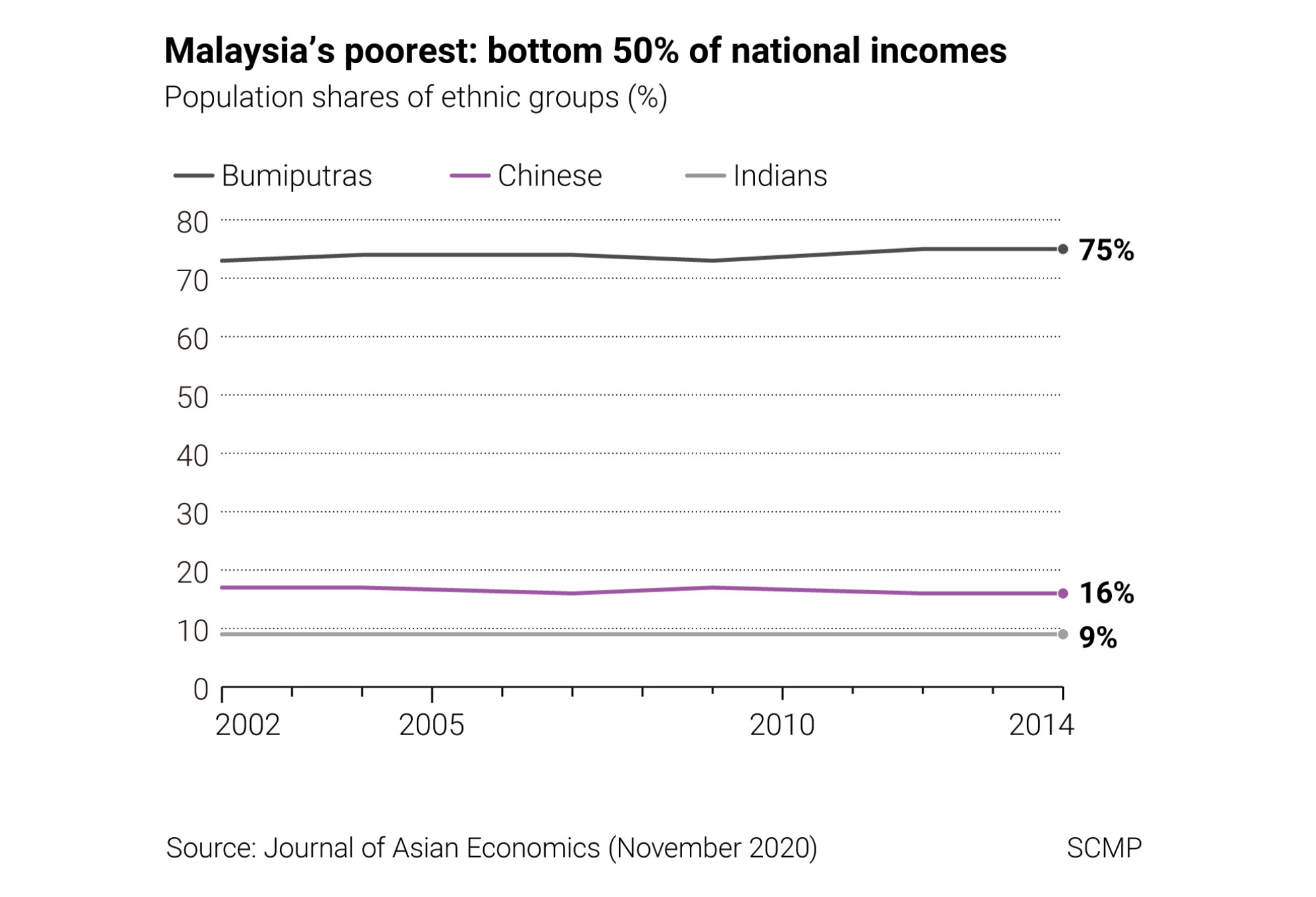

Ismail, in unveiling Malaysia’s 12th five-year economic plan, noted that the median income gap between bumiputras and the Chinese community had widened by four times in the last three decades.

The issue has meanwhile become one of the key talking points following the unveiling of the 2022 budget last week, with Lim Guan Eng, leader of the opposition Democratic Action Party, noting that the government’s allocation of 300 million ringgit (US$72 million) for non-bumiputras paled in comparison to the 11.4 billion ringgit of measures targeting the bumiputras.

In interviews with This Week in Asia, scholars and political insiders painted an almost uniform picture of the policy and the road ahead for it: the consensus view was that the NEP’s performance had been marginal at best in achieving the goals set out in 1971.

Still, given how the privileges are well entrenched, with political reprisal likely for any government that suggests their abolition, there are few who believe the NEP’s termination is on the horizon.

The likes of Anwar Ibrahim, the reformist leader of the Pakatan Harapan coalition currently in opposition, have long touted the need to pivot to a “needs-based” affirmative action programme, though the blueprint for that has been murky.

During its 2018-2020 stint in power, the alliance made little headway in stripping down the policy.

“We have to go beyond the emotive, antagonistic, intractable, and ill-informed ‘continue versus terminate the NEP’ debate,” said Lee Hwok Aun, a senior fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute who closely studies the NEP.

“We should recognise the NEP’s contributions while also being more specific and thoughtful in criticising the policy and considering alternatives,” he said.

Syaza Farhana Binti Mohamad Shukri, an assistant professor of political science professor at Malaysia’s International Islamic University, said there was little attention paid to the progress the NEP has made in propelling more Malays into the middle class.

“In other words, the gap between the haves and have-nots among Malays have narrowed. This is something to be proud of, but we seldom hear it,” she said.

Members of ethnic minority groups such as Lishana say their lived experiences offer little reason to back the NEP, even if their Malay compatriots were in favour of it.

“We are not given a fair chance at proving ourselves … our circumstances eventually end up defining us even though we try our level best not to let that happen,” she said.

Wong Chin Huat, a well-known local political scientist, said a brain drain among the country’s Chinese and Indian population and the accompanying capital flight was the “NEP’s given cost”.

The Sunway University professor said one of the key questions unanswered was that of “how long more” bumiputras required preferential treatment.

“After all, affirmative action and quotas are temporary special measures whose effectiveness is ultimately proven in their demise,” he said. “And a ‘never-ending policy’ is a failure by definition.”

Calls for reforms

Critics of the policy note they have nothing against affirmative action – which has been implemented to some success in societies around the world, including the United States.

Wong said the brickbats were reserved for the powerful United Malays National Organisation (Umno), and the means by which it had over the decades utilised the NEP to advance its political clout.

The party, to which Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob belongs, has ruled Malaysia for most of the past seven decades.

“NEP would have worked if opportunities are allocated based on merit, and previous beneficiaries and their issues are excluded from future opportunities,” Wong said. “Such an equal-opportunity scheme, however, cannot incentivise Malays to support Umno or any Malay ruling party.”

Mahathir, an Umno stalwart before he resigned and led the Pakatan Harapan alliance during its short-lived stint in power from 2018 to 2020, said the NEP would continue to be weaponised politically.

The 96-year-old was ousted following a struggle for power among the Malay elite, with Umno – which was defeated in 2018’s polls – staging a political coup against him last year after scheming with allies.

“[Politicians] are so insecure that all the time they are thinking about how to stay in their place, to remain in government,” Mahathir told This Week in Asia.

While naysayers say Mahathir was among the chief figures who abused the NEP – by handing plum corporate opportunities to loyal Malay allies – the nonagenarian suggested part of the problems lay in Malays themselves.

The former premier said Malays who were given contracts or similar opportunities wanted to “get rich quick” and passed on these opportunities to Chinese contractors who had the means to pay for them.

“The Malays should have used [the government contracts] as an opportunity to go into business, learn about the business, but they find it easier just to get the contracts,” he said.

This view, which Mahathir has long held and has been re-propagating amid the current debate, has grated some of the NEP’s proponents.

In parliament last week, Umno MP Tajuddin Abdul Rahman tacitly chided Mahathir for his views about Malays and their perceived inability to excel in business.

“Some leaders and politicians always blame the Malays, saying that after giving the Malays equity, shares, lands and projects, they would sell all of the assets, and conclude that this made the Malays lazy,” Tajuddin said, without naming Mahathir.

“Come on, man. If we are doing business, are we supposed to keep everything forever? We sell some assets off to expand our businesses. How can we make our businesses grow without some buying and selling?”

It really saddens me that my fellow Malaysians fail to see that the real enemies are the rich and privilege, not your non-bumi neighbour

Less influential citizens such as Lishana are more wary about commenting on the NEP. Unlike Mahathir, the consequence for criticising the NEP can be severe for non-bumiputras.

“The moment non-bumis question this policy, politicians turn the bumis against us, calling us outsiders as though our ancestors too didn’t give their blood, sweat and tears for this land,” she said.

“It really saddens me that my fellow Malaysians fail to see that the real enemies are the rich and privileged who hoard wealth, and not your non-bumi neighbour who is also struggling to make ends meet.”

Firdaus, the engineer, said he was hopeful that other bumiputras like him would support calls for reforms.

“We need to push our MPs on this because currently only two or three MPs bring up such issues in parliament,” he said.

A more equal Malaysia may take root “maybe not in the next 10 or 20 years, I don’t know … but I have faith it will happen”, Firdaus added.

Lee, the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak researcher, said the best course of action for now was to move on from “hyperbolic” talk about ending the NEP.

With much of government policy now incorporating the bumiputra privileges, it would be more worthwhile considering “how all these group-targeted programmes fit together, and how to make them productive and fair, and to devise other mechanisms besides group quotas”, he said.

Taking into account the likely continued dominance of Malay-centric parties in the country, Wong too offered a similar prognosis.

“Given the political realities, NEP can only be replaced not by meritocracy or market forces, but by an honestly and intelligently designed pro-Malay policy that provides better opportunities for most Malays, instead of guaranteed outcomes for a few lucky or well-connected Malays.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.