Cina losing fast in Tech war with US : nobody want to forge a chip coalition with them

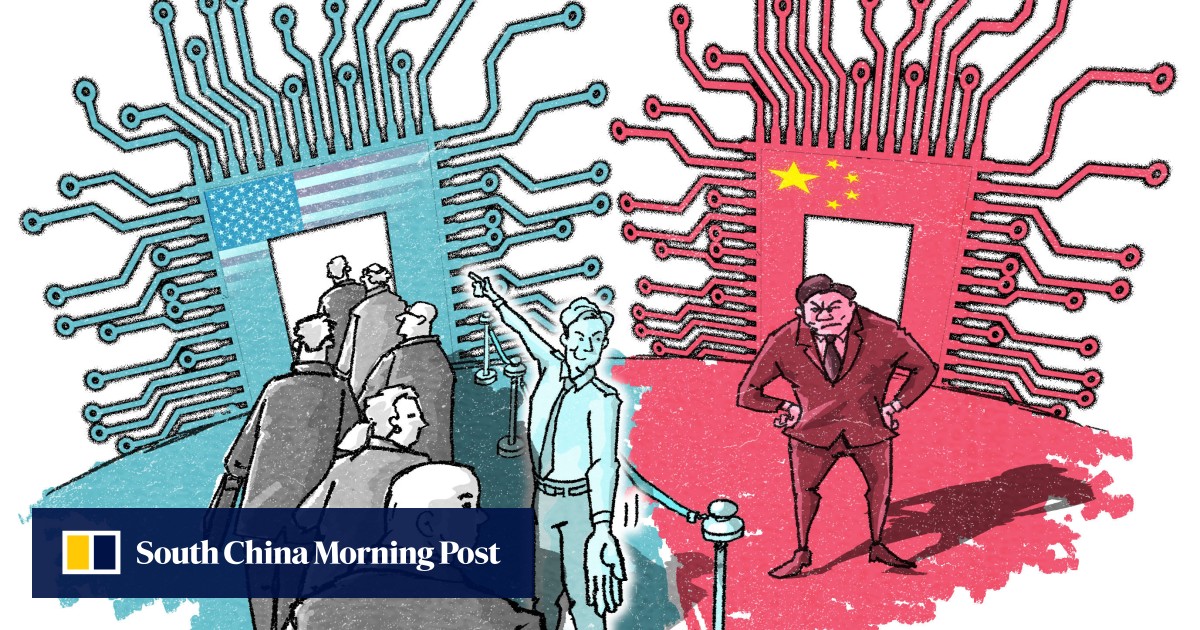

The past year has seen the emergence of a US-led coalition to thwart China’s access to advanced chips

Beijing’s plan to use Europe as a counterbalance to US semiconductor export restrictions has faltered amid rising supply chain concerns there

China set to revamp chip strategy after US curbs on advanced tech Chinese strategist Wang Xiangsui published a book in 2017 entitled One of the Three: China’s Role in a Future World, in which he described a global future that sees three main blocs emerge: North America, Europe and pan-Asia.

Chinese strategist Wang Xiangsui published a book in 2017 entitled One of the Three: China’s Role in a Future World, in which he described a global future that sees three main blocs emerge: North America, Europe and pan-Asia.

Borrowing a page from Luo Guanzhong’s literary classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Wang says China will take on leadership of the pan-Asia bloc. “China should be happy to have one third of the world under heaven,” Wang said in an interview with the Observer, a Chinese nationalist website, in late 2020.

It is open to debate whether Beijing is setting its strategy on the musings of Wang, a professor at Beihang University, but what is clear is the leadership’s push for a regional supply chain to combat Washington’s move to curtail its technology ambitions. China has forged mechanisms such as “10+3”, namely the 10 Asean members plus China, Japan and South Korea, while lobbying Europeans – the third bloc – not to fall in line with US policy.

But the past year has seen the emergence of a US-led coalition to thwart China’s access to advanced chips – which power everything from the latest smartphones to advanced weapons systems. As Washington gradually builds up an export control regime targeting China, leveraging US advantages and influence, Beijing has looked increasingly isolated.

Wei Shaojun, a senior official at the China Semiconductor Industry Association, the state-backed group representing the domestic chip industry, said at an industry conference this week that China’s chip industry will not die overnight but it cannot achieve an easy victory in this battle.

“On the one hand, we can’t be blindly optimistic and believe that we can do everything – the concept of ‘Amazing China’ is certainly out of fashion,” Wei said in published comments. “[However] we don’t have to be depressed or belittle ourselves.” Amazing China is the title of a Chinese propaganda movie from 2017 which hailed the country’s economic and technological achievements.

Washington moved quickly in 2022 to deny China access to advanced chips. With the Chips and Science Act, the US is luring chip manufacturing back to American soil with grants. To receive subsidies for plants built in America, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Samsung Electronics might not be able to build advanced facilities in China, making it much harder, perhaps impossible, for China to keep up with the US.

The US also updated export controls in October, restricting China’s access to certain advanced chips, equipment and US personnel. Furthermore, the Biden administration has stepped up diplomatic pressure on its allies to stay on the same page in restricting advanced tech exports to China.

Taiwan, the self-ruled island that China regards as a renegade province that it may take over by force if necessary, is clearly drifting away from China’s orbit. TSMC, the world’s most advanced chip foundry, is building a plant in Japan and may consider a second one there. It is also flirting with the idea of setting up its first fab in Europe in addition to its new plant in Arizona.

TSMC’s plan to spend US$40 billion to make advanced 4-nanometre chips in the US contrasts with its plan to spend US$3 billion to expand production at its Nanjing fab in mainland China, which produces mature 28-nm node chips. Apart from US restrictions, Taipei has long had restrictions barring any Taiwanese chip makers from investing in advanced technologies in mainland China to keep a technological gap of at least two generations.

Beijing is also facing a test of its relationship with South Korea. An executive at SK Hynix, the Korean chip giant that has received red-carpet treatment in Wuxi, said in October that it would consider selling its chip plant in the city if US export controls make it impossible to operate. The company subsequently denied such a plan. The local government of Wuxi has said that a Phase II investment project by SK Hynix worth 53.2 billion yuan (US$7.64 billion) has been signed.

Meanwhile Europe is pursuing its own supply chain security.

The 27-country bloc agreed a 45 billion euro (US$46.6 billion) plan to fund production of chips on home soil this month to reduce reliance on Asian manufacturers. The EU Chips Act, which is subject to EU parliamentary debate and approval in 2023, aims to boost EU-based chip production to 20 per cent of the global market by 2030 from the current level of 10 per cent.

The move reflects the EU’s heightened concerns over future supply chain risks, which may run counter to Beijing’s plan to use Europe as a counterbalance to US semiconductor export restrictions. Berlin last month blocked the takeover of German chip maker Elmos by Swedish competitor Silex, which is a subsidiary of Chinese group Sai Microelectronics.

Although the EU has refrained from singling out China as a security concern, the fact that Brussels is not doing anything to upset US policy, will have implications for Beijing’s attempts to thwart Washington’s attack, analysts say.

“On the negative side, there will be more attention in Europe on supply chain disruption that could erupt from China,” said Mathieu Duchâtel, director of the Asia programme at the Paris-based Institute Montaigne. “The EU Chips Act names the US, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan as the EU’s supply chain security partners, which makes it clear that China is considered a risk”.

Among the named partners in the EU Chips Act, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have also been tapped by Washington to form a chip alliance known as Chip 4, which is seen by Beijing as a deliberate move to marginalise China’s role in the semiconductor industry.

Singapore also serves as a hedge against supply chain risks from China for certain chip manufacturers in Asia. As such, the EU’s partnership with these liberal democracies could make China even more isolated.

Mergers and acquisition activity by Chinese companies in the European tech sector has already come under greater scrutiny.

The UK government in November demanded that the semiconductor firm Nexperia sell at least 86 per cent of Welsh wafer fab Nexperia Newport Limited due to a “risk to national security”.

Nexperia is a Dutch subsidiary of China’s Wingtech technology. Wingtech obtained 79.97 per cent of Nexperia’s shares in 2018, becoming its largest shareholder and bought the rest of Nexperia’s shares in 2020. During the previous year, Nexperia also invested in Nexperia Newport Limited (then Newport Wafer Fab), becoming the company’s second-largest shareholder.

However, Duchâtel said the EU Chip Act’s direct impact on China is limited for now as economic ties between the country and Europe remain strong. Both EU exports to and imports from China increased between 2011 and 2021, according to official statistics from Eurostat. Chinese investment in Europe (EU-27 plus the UK) increased 33 per cent to 10.6 billion euros in 2021, the first pickup from a downward trend since 2016, according to data from Rhodium Group and MERICS.

Meanwhile, one of the key European players in the US-China chip war is ASML, the Dutch firm with a quasi-monopoly in lithography systems – necessary for advanced chip production. In the face of US demands for further export restrictions to China, Dutch foreign trade minister Liesje Schreinemacher pushed back, saying the US cannot decide the country’s policy and that the Netherlands “will not copy” US curbs on exports of chips and chip-making technology to China.

However, China still has geopolitical hurdles to climb. According to a Bloomberg news report this month, citing unidentified sources, Japan and the Netherlands have agreed to tighten export controls on advanced chipmaking tools to China. If ASML is pulled within the confines of such an agreement, then this could even impede China’s plans to expand capacity of plants handling mature technology nodes.

And although Beijing has filed a dispute at the World Trade Organization (WTO) against the US chip export controls, Washington has blocked appointments to the WTO’s top ruling body on trade disputes in recent years, meaning that some rows never get settled.

Korean chip maker SK Hynix says it may sell China fab under US pressure

Arisa Liu, a senior semiconductor research fellow at the Taiwan Institute of Economic Research, said semiconductor equipment and materials suppliers from the Netherlands and Japan “might not be on the same page with the US” in sanctioning China due to their own business interests.

“In the short term, it is still to be seen whether the US can leverage both a carrot and stick to form an alliance against China, although we expect hurdles to remain quite high for European countries to ship semiconductor equipment to China or sell semiconductor businesses to mainland China companies,” Liu said.

Meanwhile, the US is set to enhance and widen its export controls in 2023 to counter China, according to analysts at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank.

“If the Dutch and the Japanese do not go along willingly, the Biden administration could threaten to take extraterritorial measures”, they noted. The US could also extend export controls into other technology areas that are “fundamental to United States technological leadership and therefore national security” such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, quantum computing and advanced clean energy.