Xi Jinping’s empty dream city shows limits of his power, even in China

In 1979, Deng Xiaoping drew a circle on the map around China’s southern coast and created Shenzhen, an experiment in capitalism, according to a popular ode to the former leader.

Nearly four decades later, Xi Jinping unveiled his own ambition for an era-defining city, this time perched on the outskirts of Beijing.

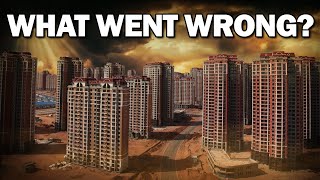

Xiongan was billed as a gleaming, high-tech metropolis that would serve as a release valve for the crowded Chinese capital — "a model city in the history of human development.”

The ruling Communist Party has since spent some 610 billion yuan ($85

billion) on the city, more than double the cost of the Three Gorges

Dam. On former cornfields now stand a train station, office buildings,

residential compounds, five-star hotels, schools and hospitals.

The ruling Communist Party has since spent some 610 billion yuan ($85

billion) on the city, more than double the cost of the Three Gorges

Dam. On former cornfields now stand a train station, office buildings,

residential compounds, five-star hotels, schools and hospitals.

Just one thing is lacking: residents.

When Bloomberg visited on a weekday this month, a highway into the

city was almost empty. In the city center, few shops and restaurants

were open on streets lined with brand-new government headquarters,

office buildings, residential compounds and hotels.

When Bloomberg visited on a weekday this month, a highway into the

city was almost empty. In the city center, few shops and restaurants

were open on streets lined with brand-new government headquarters,

office buildings, residential compounds and hotels.

Workers at a research institute under pressure to move from the capital said they were worried about the quality of education for their children. Four Beijing-based universities that announced relocation plans in 2022 are now aiming to set up a secondary campus instead.

"I worked hard in the college entrance exams to come to Beijing, not to Xiongan,” said a first-year student at the China University of Geosciences, who asked for anonymity to speak to avoid official reprisals.

Xi trumpeted the city’s progress in his annual new year speech, saying it was "growing fast” and helping to revitalize northeastern China. Last year, he warned against resisting the project, calling it "totally correct.”

"People must move if needed to,” he said during a May visit to the city with top leaders including Premier Li Qiang and chief of staff Cai Qi.

But people are "voting with their feet,” said Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

"This resistance is based on real-world interest. If you cannot make their interests align with your interest, then of course you can’t make it happen,” Wu said. "Xi’s power still has limits after all.”

Unlike Deng’s laissez-faire approach that led to Shenzhen’s disorderly but colossal growth, Xi has opted for meticulous planning to help his city avoid problems dogging other areas.

For example, Xiongan has imposed strict controls on home prices to fend off speculators, adhering to Xi’s mantra that "housing is for living, not for speculation.” Last year, the city banned developers from selling homes they haven’t built, a major departure from the pre-sale model common across China that fueled a housing bubble.

The city is being selective about which industries it welcomes, encouraging companies working in information technology, biomedical and new energy sectors and eliminating what it calls traditional industries. That’s unlike Shenzhen’s free-wheeling approach that attracted millions of migrant laborers and entrepreneurs.

A museum dedicated to the city’s development touts how it has been centrally planned. Many essential utilities such as electricity cables are placed in large underground tunnels to facilitate easy maintenance and keep the city streets neat. A central hub monitors traffic digitally to prevent jams that clog up cities such as Beijing and Chongqing. Although, there’s currently little traffic for the system to control.

Xi has time for the city to get going.

Xiongan has a midcentury target for completion and a 2035 near-term development milestone. In 11 years’ time, the city is expected to handle some of Beijing’s non-capital functions and become a "high-level modernized socialist city” — with digital sectors making up at least 80% of the local economy, 45% of urban waste recycled, and full high-speed internet coverage, according to government documents.

Its success in reaching those goals will be linked to Xi’s own legacy. Quotes from the Chinese leader are plastered across red billboards around the city, extolling it as "a project of national priority” and "a plan of millennial significance.” Those banners are hung beside the almost deserted train station, which is surrounded by a field of chest-high grass and unfinished buildings.

Big cities’ appeal often lies in their organic street life, said Covell Meyskens, an academic who has written about government planning in China. "Planned smart cities are supposed to be the place of the future,” he added, but without those human trappings, "nobody wants to live there.”

The tensions surrounding Xiongan, and its elevated status for the Communist Party, came to a head in the summer when northern China was hit by its worst floods in decades.

Officials ordered all-out efforts to protect Beijing and the sparsely populated Xiongan, calling them the "top priorities for flood control” — even if that meant diverting water to flood neighboring cities and villages, leaving thousands of people stranded for days.

That decision prompted a rare protest outside local government offices in Bazhou, Hebei, where dozens of residents challenged the authorities’ claim that rain, not discharged water, destroyed their homes.

The deluge also brought to the fore criticism that the site was poorly chosen because it’s historically prone to flooding due to its low elevation. Construction of permanent structures had been banned in the area after a major flood in 1963, according to Xu Kuangdi, a government expert on Xiongan’s planning.

It was exactly because of that lack of buildings that officials decided to build there, according to state media reports.

Xiongan still has decades to go before its success can be tested, and many Chinese cities once ridiculed as ghost towns have later been populated, as industry moves in.

Even Deng’s celebrated city was mired in political controversies and economic challenges in its early years, according to Du Juan, an architecture professor at the University of Toronto and author of "The Shenzhen Experiment.”

That special economic zone’s rapid development coined the term "Shenzhen speed,” as the exporting hub rode on the back of China’s manufacturing boom and breakneck growth.

As the Asian powerhouse’s economic growth slows, Xiongan will have no such luxury.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.