Syrians Pay a Heavy Price for Assad’s Victory

Even his Alawite base is growing disaffected.

In 1970, then-Syrian Defense Minister Hafez Assad staged a military coup and, a few months later, won the presidency in an uncontested vote. He became the Sunni-majority country’s first president from the Alawite sect, which many Sunnis considered a heretical branch of Islam. Assad pursued sectarian politics but avoided talking about sectarianism directly, referring instead to pretentious slogans such as Arab nationalism, national unity, anti-Zionism and resistance to imperialism. He founded his regime on a strong Alawite base of support and clamped down on the opposition, including the Alawite leftist elite, which rejected his tight grip on power, fearing they would pay a heavy price for it later. Their fears were validated when Assad’s son, Bashar, succeeded him in 2000. He violently crushed an uprising in 2011, leading to a more than decadelong civil war. The fighting has now subsided and Bashar Assad remains in power, but his victory has taken a substantial toll on the people of Syria.

Alawite Foot Soldiers

Drawing on the historical mistreatment suffered by the Alawites, the Assads planted seeds of fear that the Sunni majority would overrun the sect in order to secure its loyalty. Hafez Assad granted Alawites privileges they never dreamed of and promoted them to senior positions in the government. The Alawite dynastic republic he established hinged not on the rule of law but on a repressive sectarian system that hijacked the state and ruled by brute force. He and his son refused to open up to other elements of Syrian society, demanding that Alawites control every component of the state, including the security services, the army and the judiciary. By the time he died in 2000, Hafez ensured that there would be no Alawite opposition to Bashar.

When a peaceful uprising erupted in 2011, the Alawites backed Bashar Assad’s crackdown on the protesters, which included the use of excessive violence. After he realized the protests would not subside, he released Islamic fundamentalists from his prisons. He essentially allowed them to target Alawites in the villages north of Latakia to ensure that the sect would turn to him for protection and give him its unwavering loyalty, bonding its fate with that of the regime.

However, disaffection with Assad’s regime began to grow, even among the country’s troops, most of whom are young Alawite men. The conflict has so far produced more than 250,000 dead, missing and disabled soldiers. Many Syrian soldiers grew to see themselves as nothing more than pawns used to keep Assad in office. The anti-Assad Free Alawite Movement emerged after the 2011 uprising turned into a civil war. It anticipated a dark future for the sect, which couldn’t dissociate itself from Assad, viewing him as the lesser of two evils. Some demonstrated in 2011 against the Assad family and its harsh repression. In 2013, Alawite opposition members gathered in Cairo to express their desire to cooperate with the anti-regime uprising. In the coastal city of Latakia, a regime bastion, activists tried to prevent young people from joining the army ranks.

For many Alawites, however, the costs of supporting the regime have exceeded the benefits. Assad’s opponents within the sect, which represents less than 11 percent of Syria’s total population, have concluded that their sacrifices were merely for the sake of keeping four Alawite families of no more than 250 people in power. Many Alawite families have lost all their children and have been left without a breadwinner or financial support from the regime. Assad and his wife showed little respect for fallen Alawite fighters who defended his government, offering their grieving families cheap wall clocks or boxes of oranges as a tribute. However, the heavy losses have failed to disengage Alawites from the Assad regime. Syrian opposition groups bet wrongly that Alawite discontent would lead to Assad’s ouster. While they openly express their anger at the corruption of the government in Damascus, Alawites feel helpless and believe that only foreign countries, such as the U.S., Russia, Iran and Turkey, can resolve the conflict.

Cost of War

Alawites aren’t the only ones who have paid a heavy price for the conflict. Since the start of the war, conflict-related deaths have reached 700,000, including 570,000 killed directly by the fighting. Over 13 million people became displaced, half of them outside of Syria. Some 2.4 million children – more than a third of the country’s school-aged youth – do not have access to education, and roughly a similar number of Syrian refugee children also are out of school. The lack of education will be disastrous in the long term as millions of children will lack the skills and knowledge necessary to advance the Syrian economy.

The war also changed the shape and structure of the Syrian state at all levels, including the economy. The country’s gross domestic product dropped from about $60 billion in 2011 to $11 billion today, and the local currency collapsed after the exchange rate fell from 50 Syrian pounds against the dollar to more than 8,550 today. Some 90 percent of the population lives in poverty, while more than 85 percent of workers are unemployed and about 60 percent of people suffer from severe food insecurity. The war wiped out Syria’s agricultural sector, forcing the country to rely on food imports. It destroyed industry and half of the country’s infrastructure. It also forever changed its demographic composition, transforming Sunni Arabs from a majority to a disadvantaged minority.

Since the beginning of the uprising, the international community, especially the U.S. and the EU, has imposed economic sanctions on the Syrian regime. But the country has been in a political stalemate since the end of 2019. The fighting has nearly stopped, Assad’s regime remains in power, and no political solution has been realized. Thus, the country’s reconstruction phase faces many obstacles that could delay it for years. The cost of rebuilding Syria could exceed $800 billion, but it will be possible only with an international effort, specifically from the U.S., which has the means to pressure local and foreign players. These external actors won’t engage with Assad still in power. International sanctions are still in place, and those responsible for human rights abuse haven’t been held accountable. It makes little sense to talk about reconstruction before addressing the root causes of the conflict, the most important of which are political, economic and social injustices. Addressing these factors will be a gradual, long-term process that must include various segments of society. Moreover, the instability and fierce competition between different wings of the Syrian regime over the country’s wealth and assets make potential investors unwilling to fund reconstruction efforts.

The most critical challenges facing Syria’s recovery are political. Assad’s regime continues to rule chunks of Syrian territory, and Western powers would require Assad’s compliance to implement U.N. Security Council resolution 2254, which calls for establishing a constitution and forming a transitional governing body with broad powers. This arrangement would lead to Assad’s departure, followed by elections monitored by the United Nations.

Iran Wins

Iran, meanwhile, stands to gain from its involvement in the war. In 2012, when rebels controlled 80 percent of Syrian territory, Tehran rushed to the Assad regime’s aid. By the time the heavy fighting subsided, especially after the opposition retreated to Idlib province and the Islamic State was defeated, Iranian militias had gained vast influence in several regions of the country, which Tehran has exploited to further its interests in the region. After Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed last March to resume diplomatic relations, Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi arrived in Damascus, accompanied by a large delegation that included the ministers of construction, defense, oil and communications, to promote economic ties. Despite indications to the contrary, the prevailing opinion in Iran is that Syria has entered the reconstruction stage of its recovery. Tehran, which stood by Damascus’ side throughout the war, now believes it can profit from these efforts.

The Iranians control a significant percentage of the principal sovereign investments in Syria. Iran obtained deferred assets that guarantee its influence in the country for years to come and complicate efforts to rehabilitate Syrian infrastructure. It also controls strategic projects involving oil, phosphates and ports, which shackles the state’s decision-making capability. With both Iran and Russia claiming the most important infrastructure initiatives, only minor and unappealing projects are left for other bidders to explore.

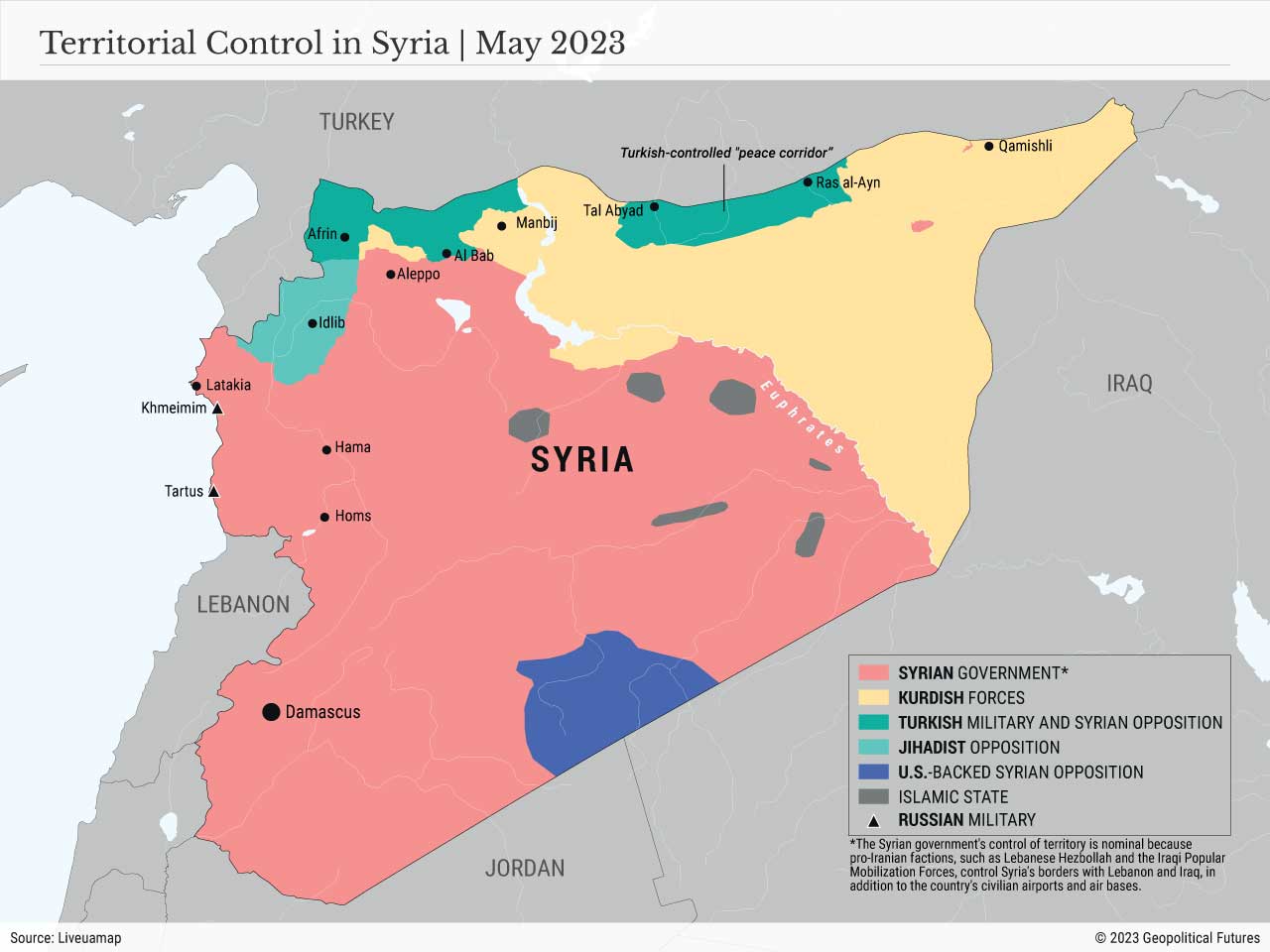

Though the government in Damascus nominally controls Syria’s territory and borders, the real power belongs to Iran and its Shiite proxies. Pro-Iranian forces control all air bases in the country. Iran is also actively trying to maintain its presence on Syria’s borders with Iraq and Lebanon – to preserve supply routes for Hezbollah, its most prominent proxy in the region – in addition to the border with Jordan close to the Golan Heights.

Fractured Society

Though Assad survived politically, he now presides over a divided population, half of which is internally or externally displaced. Four foreign armies control different segments of the country, and the Kurdish Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria occupies one-quarter of Syrian territory. There are no organized political or social forces within Syrian society, which is divided along sectarian, regional and tribal lines. Even the ruling Baath party has no legitimacy, relying exclusively on coercion to continue its rule. Meanwhile, Western sanctions, especially those imposed under the U.S. Caesar Act, embolden Assad and help to tighten his grip on power.

For Alawites, there was no real alternative to the regime, as the Sunni-led opposition was sectarian and exclusionary. This helped bolster Assad’s control, as he invoked the threat of radical Islam from the first day of the protests. Though Alawite discontent has somewhat eroded the regime’s base of support, it will not lead to major unrest.

The Assad regime’s response to the uprising was short-sighted and foolish. Assad could have quickly defused the protests by displaying a gesture of goodwill, especially since most Syrians still perceived him positively at that point. Instead, he viewed the uprising as a conspiracy against his regime. His mismanagement of the crisis led to more than a decade of bloodshed and destruction, eventually handing the country over to Iran on a silver platter.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.