Indonesia is distrustful of China’s new development, security initiatives

In theory, China’s Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative both have a lot to offer Southeast Asia’s largest economy

But Beijing needs to do more to allay Jakarta’s concerns about debt, sustainability, environmental impacts – and peace in the South China Sea

It’s no secret that China wants Indonesia to sign up to its new global development and security initiatives, but Jakarta is going to take some convincing before it takes the plunge.

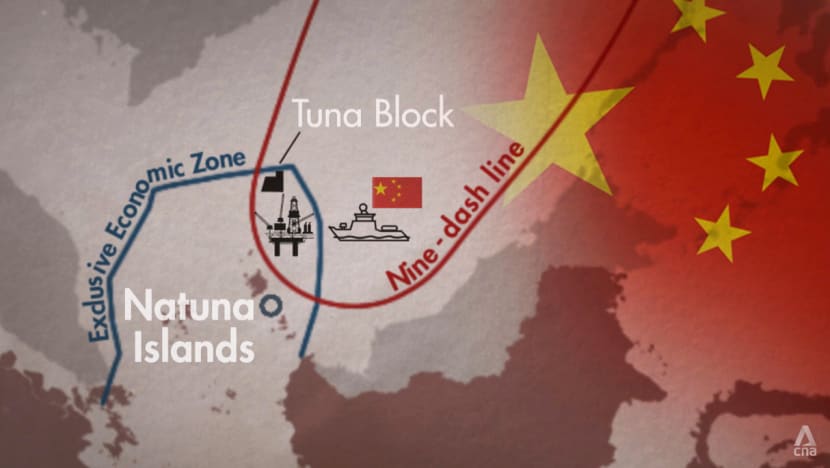

On paper, Beijing’s Global Development Initiative (GDI) and Global Security Initiative (GSI) both have a lot to offer Southeast Asia’s largest economy. Chinese officials know this, and have been actively promoting the strategies to their Indonesian counterparts any time they get a chance. Yet Indonesia has so far been cautious in voicing its support – a wariness born not only of its experiences with Beijing’s earlier Belt and Road Initiative, but also its concerns about unsustainable lending and lingering issues surrounding overlapping claims in the disputed South China Sea.

Yet Indonesia has so far been cautious in voicing its support – a wariness born not only of its experiences with Beijing’s earlier Belt and Road Initiative, but also its concerns about unsustainable lending and lingering issues surrounding overlapping claims in the disputed South China Sea.

The GDI, first unveiled by Chinese President Xi Jinping at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2021, promises to support emerging economies in poverty alleviation, public health and sustainable development, among a host of other issues. Unlike belt and road infrastructure projects, which mostly aim to grow global trade, the GDI is focused on knowledge transfer and capacity building through the provision of grants and development assistance. It also has a broader scope, going beyond bilateral agreements to include potential partnerships with NGOs and the private sector.

Unlike belt and road infrastructure projects, which mostly aim to grow global trade, the GDI is focused on knowledge transfer and capacity building through the provision of grants and development assistance. It also has a broader scope, going beyond bilateral agreements to include potential partnerships with NGOs and the private sector.

Xi was keen to promote the GDI to Indonesian President Joko Widodo during their July meeting in Beijing. But there are concerns in Jakarta that this new Chinese development initiative will result in the same delays, cost overruns, safety issues and environmental destruction seen under the earlier belt and road strategy.

A China-funded dam in North Sumatra, for example, has come under fire for threatening to wipe out the Tapanuli orangutan, a critically endangered species of great ape that was only discovered in 2017. Recent worker deaths during construction of the delayed Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway, meanwhile, have raised fresh concerns about worker safety on Indonesian belt and road projects.

China also really wants Indonesia to be involved in its other new initiative, the GSI first proposed by Xi at the Boao for Asia Forum last April as an alternative to US-led security norms. A month after it was announced, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi publicly promoted the initiative during a virtual meeting with Luhut Binsar Panjaitan, Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment.

But the Indonesian government remains wary of dealing with China on security issues, as noted by international relations expert Teuku Rezasyah from Padjadjaran University.

Despite being touted as an “Asia for Asia” approach that is free of interference from outside actors, there are fears that the GSI will be skewed towards China’s interests. This is especially true in its supposed rejection of unilateral action, which stands in direct contrast to recent Chinese actions in the South China Sea.

Beijing’s critics, particularly those in the West, have repeatedly suggested that it does not respect international laws or norms when it comes to the disputed waterway.

A key reason for this line of argument is China’s non-recognition – and hence non-adherence – to the 2016 ruling by an international arbitration tribunal that found its expansive nine-dash line claim to the South China Sea had no legal basis. China did not take part in the proceedings and insists that the ruling is not legally binding.

Also of concern to Beijing’s critics are the activities of its coastguard vessels, which have repeatedly harassed foreign-flagged craft in the disputed waters, including a close-call with a Philippine ship in March last year.

A recent survey by the Centre for Indonesian Domestic and Foreign Policy Studies found that many in Southeast Asia are leery of Beijing’s ambitions in the South China Sea, especially those living in countries with clashing territorial claims.

Allaying concerns

So what can China do to put these fears to rest and ensure that both its new initiatives are warmly received by the people and parliament of Indonesia?

First, it must take a more active role in promoting peace and negotiating a long-awaited code of conduct for the South China Sea. If Beijing shows that it can respect and comply with such a code, then its GSI will be more readily accepted by all Southeast Asian nations, Indonesia included.

Second, China must demonstrate that the societal and environmental issues associated with its belt and road projects will not occur again under the GDI. It can achieve this by adopting more sustainable development strategies and approaches.

Third, Beijing must be more transparent regarding investments and debt. Many in Indonesia are fearful of the country falling into a Chinese “debt trap” – even if academics such as Lee Jones, a reader of international politics at Queen Mary University of London, and Shahar Hameiri, an international-politics professor at The University of Queensland, contend that this is more media-spun narrative than reality.

Indonesia and other Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ member states are sure to think long and hard before publicly expressing their support for either of China’s new initiatives. The onus is now on Beijing to demonstrate the benefits.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.