As China-Australia ties fray, who is shaping Canberra’s increasingly hawkish policy on Beijing?

- Prime

Minister Scott Morrison and his cabinet rely on a roster of key

advisers and appointees known for their focus on national security and

tough China stance

- These

include the nation’s top spy, Andrew Shearer; Nick Warner, a former

diplomat and intelligence operative; and former national security

adviser Justin Bassi

The tough approach of Morrison’s inner circle has coincided with a serious deterioration in Sino-Australian relations

. While they have been strained in recent years, ties have taken a sharp dive since Canberra last year called for an independent international inquiry into the origins of Covid-19, prompting Beijing to retaliate with billions of dollars of restrictions on Australian exports. In recent weeks, senior Australian government figures have invoked the spectre of war, including defence minister Peter Dutton, who in April said Australia could not rule out the possibility of a conflict with Beijing over Taipei.

Key figures shaping Australia’s China policy include Andrew Shearer, Morrison’s former Cabinet secretary who now serves as the nation’s top spy as director general of the Office of National Intelligence (ONI); Nick Warner, a former diplomat and spy who now works as a consultant to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC); and Justin Bassi, chief of staff to foreign affairs minister Marise Payne and a former national security adviser to ex-prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, Morrison’s immediate predecessor.

Shearer, a national security adviser to former prime ministers Tony Abbott and John Howard, is known for publicly expressing concerns about Beijing’s strategic intentions years before such worries would become default thinking in Canberra.

In a 2010 analysis for the Lowy Institute think tank, Shearer warned that Australia’s reliance on China as its biggest trading partner made it “increasingly difficult to align our strategic policies with our economic interest”, and argued it was not “unreasonable for Australians to be cautious about the underlying motives of major Chinese investments in sectors of strategic importance to Australia”.

Canberra banned Chinese tech giant Huawei from Australia’s 5G network on national security grounds in 2018 – the same year it passed anti-foreign interference laws seen as mostly aimed at Beijing – and in April vetoed the state of Victoria’s agreement to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s global infrastructure development strategy. Australian officials are also currently considering whether to rip up a 99-year lease to the port of Darwin that was awarded to Chinese-owned Landbridge Group in 2015.

Shearer – who spent two years working at the influential Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington – is also known as a strong advocate of cooperation with the United States

and other like-minded countries to counter China’s growing power and influence. In a 2017 opinion piece, he criticised former prime minister Kevin Rudd for his 2008 decision to withdraw Australia from the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – or Quad, which also involves the United States, India and Japan – as a gesture of goodwill towards Beijing.“Rudd – a bona fide China expert – should have known that China’s authoritarian leaders have no respect for weakness and are quick to pocket gratuitous concessions,” Shearer wrote.

John Blaxland, a former intelligence officer who is now a professor at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the Australian National University, described Shearer as a “strong believer in the US alliance, and strong supportive measures to bolster America’s engagement in the region, and that includes the Quad”.

“He’s a trusted conservative political figure,” Blaxland said. “His judgment is highly regarded in inner circles.”

The ONI declined to comment on this story.

‘HARD-HEADED APPROACH TO NATIONAL SECURITY’

Warner, a former ambassador to Iran and director general of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service, the Australian equivalent of the CIA, is considered another key player in setting the tone of policy on China.

The veteran public servant has worked as a consultant for the government since stepping down last year as the inaugural head of the ONI, which Turnbull established in 2017 to advise the prime minister on national security.

Blaxland described Warner’s reputation as “being a little bit softer and less categoric, perhaps” compared with colleagues such as Shearer, despite Warner’s extensive background in espionage.

Bassi, who is Turnbull’s former national security adviser and also worked in the ONI, is also widely seen as hawkish on China as well as being an influential voice as a close confidant of the country’s top diplomat.

A former senior Australian government official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, described Shearer and Bassi as both having a “very tough-minded, or hard-headed, approach to national security, and a strong sense of Australia’s national interest”.

The ex-official said all three figures were influential and had important roles “shaping the way the government thinks about our region and the various challenges that China presents”.

Trade ‘only one part of the battle‘ in China-Australia dispute, says legal expert Bryan Mercurio

Among the voices believed to provide a moderating influence is Michelle Chan, who was last year promoted from Morrison’s national security adviser to deputy secretary of the ONI. Allen Behm, a former senior defence official and adviser to shadow foreign affairs minister Penny Wong, described Chan, a former ambassador to Myanmar, as able and more nuanced than some of her peers.

“She has, as I understand it, a reputation for being very much more subtle in the way in which she deals with international policy issues,” said Behm, head of the International and Security Affairs programme at The Australia Institute think tank, which describes itself as independently funded by donations and research commissions from philanthropic trusts, individuals, businesses, unions and non-government organisations.

“And I have heard that she does moderate, in some respects at least, the dialogue that goes on in the prime minister’s office,” he said. The Office of the Prime Minister did not respond to a request for comment.

While there is little disagreement that hawkish figures are influential in Canberra, there are divergent views about the extent to which their perspectives have spurred a tougher line on Beijing compared with China’s increasingly aggressive foreign policy.

The former Canberra official said Shearer, Warner and Bassi were “not outliers” within the foreign policy establishment, describing a “broad consensus” on how Canberra should manage ties with Beijing.

“From an Australian perspective, a very mainstream one, we have genuine concerns about China’s ambitions in the region, the way it conducts its foreign policy, the way it’s now advancing its interests in the region,” he said. “We have genuine concerns about some of the things it is doing inside Australia and to Australia, whether it’s cyber or foreign interference or disinformation, and there’s now just a very big values gap.”

Blaxland of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre said the hawkish elements were both driving and reflecting a changed outlook on China.

“They are reinforcing it,” he said. “They have been privy to it for years. These are people who have seen the classified reports on the fallout of Chinese assertiveness in Australian political and economic life. They are reacting to it and they are quite determined.

‘AT REAL RISK OF LOSING CONTROL’

James Curran, a former government official who is currently a history professor at the University of Sydney, said, however, that Canberra had “gone out ahead of other countries”, including the US, on China policy.

“Australia’s position comes from a swirling mix of doubts about American resolve in Asia – even as Biden talks tough on [Beijing] – and the hyping of the China ‘threat’ narrative,” said Curran, who has held roles in the DPMC, defence department and the Office of National Assessments, the precursor to the ONI.

“Those two factors work in tandem. The prime minister slips the word ‘peace’ into the occasional statement but this is drowned out by his ministers, public servants and backbench. Morrison is at real risk of losing control of Australia’s China policy.”

Other prominent voices that have pushed a tougher line on Beijing include Department of Home Affairs secretary Mike Pezzullo, Assistant Minister for Defence Andrew Hastie, and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute think tank, which is part-funded by the Australian, US and British governments.

Backbenchers taking a similar stance include “wolverines” such as Senator James Paterson and MP Tim Wilson for the Coalition, and Senator Kimberley Kitching for the opposition Labor Party. Ted O’Brien, a Mandarin-speaking government MP in Queensland, has also pushed a tougher line, calling on Canberra to align with other countries to use boycotts and sanctions to counter Beijing’s economic penalties.

Prior to the Morrison administration, key Turnbull adviser John Garnaut in 2016 led a secret inquiry into Chinese interference that inspired the landmark anti-foreign interference legislation that would mark the beginning of a years-long decline in Sino-Australian relations.

Garnaut, a former foreign correspondent based in Beijing, is currently advising a number of Australian universities on managing foreign interference risks amid heightened government scrutiny of the tertiary sector’s exposure to Chinese influence. He did not respond to a request for comment.

Behm of The Australia Institute said the key players within Morrison’s inner circle lacked an understanding of the “almost infinite complexity” of China as a rising power, economy and culture.

01:51

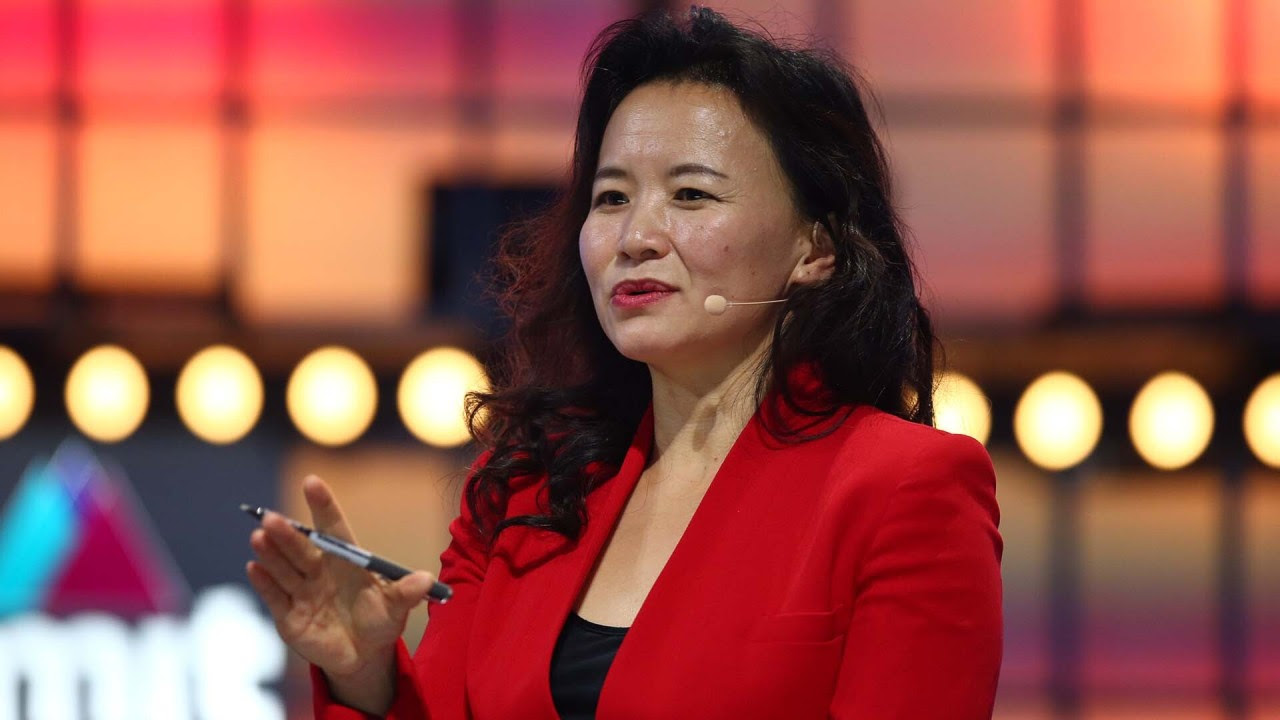

Australian journalist Cheng Lei formally arrested in China for ‘illegally supplying state secrets’

Australian journalist Cheng Lei formally arrested in China for ‘illegally supplying state secrets’

“They’re looking at all of China’s actions simply through the lens of threat and fear and anxiety without really looking at the constraints that China itself has in being able to assert itself, particularly through the use of military and weapons systems in those areas where such action would have unforeseeable consequences,” he said. “They dismiss the leadership of China as totally authoritarian, autocratic and merely a dictatorship without understanding that the leadership of China and the leadership of the Communist Party of China are actually clever and politically experienced people.”

Behm said he did not condone Beijing’s actions, but Canberra could not assume that China was “insane or evil” because it was pursuing national and global power.

Some observers have suggested the national security establishment has been allowed to effectively take over policy to the detriment of other considerations such as the economy.

In an essay in the Australian Financial Review last month, veteran journalist Max Suich said the China threat had been exaggerated through an “unprecedented and sophisticated campaign providing the media with leaked ‘scoops’ of material from the intelligence agencies about Chinese subversion operations”.

Gareth Evans, who served as foreign affairs minister from 1988 to 1996, said Australia’s intelligence community appeared to be “more obviously speaking with a single voice” than in the past.

“It is always crucial that this material be both contestable and contested, and I am no longer sure that it is,” he said, lamenting an apparent decline in the influence of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

“While there are still some good people in DFAT … they seem to have lost all influence in moderating the government’s loopier behaviour,” he said. “Reminds me of the old line about a husband being a lover with the nerve extracted – this is a once-great department with no visible remaining nerve at all.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.