Demythologizing the Shaolin Monks

Demythologizing the Shaolin Monks

Just about everything you think you know about the Shaolin Monks was made up for tourists.

Today we're going up into the misty mountains of China's Henan Province, to find an ancient red Zen Buddhist temple. It is the home of the Shaolin, said to be the creators of kung fu, and the very birthplace of Zen Buddhism itself. This ancient and mysterious order of orange or yellow robed monks have studied here for centuries, and are the most accomplished of all martial artists, able to withstand any blow or attack. At least, so the story goes.

Americans got their first big exposure to the Shaolin monks with the 1970s TV series Kung Fu starring David Carradine. In the intro, we see him as a young monk completing a rite of passage ceremony where he had to lift and move a heavy cauldron filled with glowing cinders, and in doing so his arms were branded with a dragon and a tiger. For all his quiet wisdom and serenity, this monk had fighting skills that were unsurpassed. It was a combination that was deeply attractive to Western audiences of the seventies obsessed with the superiority of Eastern enlightenment over Western materialism.

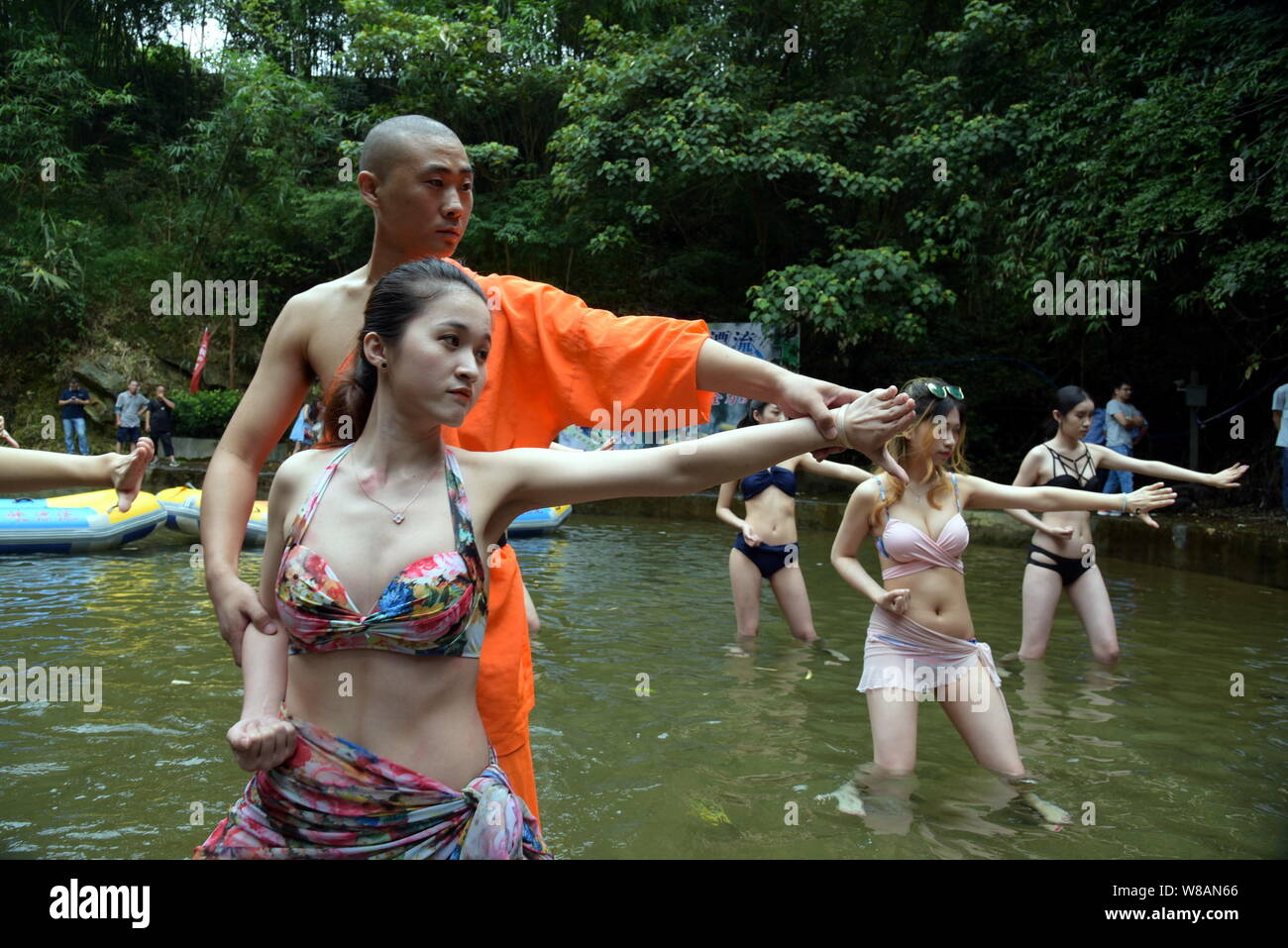

This obsession has not been lost on marketers. Today you can go to virtually any city in the world and find a Shaolin martial arts school. You can go to a theme park or aboard a cruise ship and catch a live stage show of Shaolin masters demonstrating their amazing abilities. Never mind that almost none of these have any connection with the actual Shaolin Temple. China is a land where counterfeit Apple Stores outnumber real ones by hundreds to one; and just as we'd expect, the name Shaolin is exploited every bit as much. But even the real Shaolin Temple licenses its name to anything and everything, even including instant noodles, coffee, take-out foods, tea, car tires, beer, and cigarettes, pulling in untold volumes of cash. The Shaolin Temple itself is little more than a tourist attraction now: take a five-minute group kung fu lesson with everyone else from the tour bus, and pose for your group photo holding your certificate; then stay for the live show, a mind-blowing combination of Cirque du Soleil and New Year's Eve at Times Square. It's little wonder that many serious martial artists hold the modern Shaolin in such disdain: the authentic ones sold out to be pawns for official government public relations, and the inauthentic ones exist only to cheat extra dollars out of naive martial arts students impressed with the venerable name. In short, it's very, very easy to find lots of uncomplimentary things to say about the modern Shaolin.

But even if all of that's true, it merely poisons the well of the

Shaolin monks' actual history and actual abilities. It's still valuable

to know these things; real history offers real insight and real lessons.

But we find we quickly come up against a roadblock. It comes in the

form of 1500 years of shifting governments and recycled, repurposed

histories. It's trivial to look up and read about the history of the

Shaolin, but the more scholarly the research, the more likely you are to

encounter qualifications like "many historians consider this to be

fictional" or "these stories are more accurately considered traditions

than facts". But one thing we can say for sure: attempts to nail down

the history of the Shaolin past 1928 are fraught with peril.

But even if all of that's true, it merely poisons the well of the

Shaolin monks' actual history and actual abilities. It's still valuable

to know these things; real history offers real insight and real lessons.

But we find we quickly come up against a roadblock. It comes in the

form of 1500 years of shifting governments and recycled, repurposed

histories. It's trivial to look up and read about the history of the

Shaolin, but the more scholarly the research, the more likely you are to

encounter qualifications like "many historians consider this to be

fictional" or "these stories are more accurately considered traditions

than facts". But one thing we can say for sure: attempts to nail down

the history of the Shaolin past 1928 are fraught with peril.

1928 was a pivotal year for China. It was the end of the warlord era, and the beginning of the reign of Chiang Kai-shek. For several years, growing Republican sentiment had been separating the warlords, but with a complexity far beyond the scope of a Skeptoid episode, combining ideologies, religious differences, and political changes. Suffice it to say that in March of 1928, the Shaolin found themselves with the wrong loyalties at the wrong time, the temple was overrun along with the surrounding city, and some 200 monks were killed. Elements of the National Army spent weeks systematically burning and destroying this symbol of Old China. Modern histories are always quick to point out that this loss included their library; more about that soon.

Prior to the 1928 destruction, the true history of the Shaolin Temple is probably quite mundane compared to its traditional history, which is filled with many more battles and cases of destruction. In particular it's said that the Qing Dynasty, sometime in the 1600s or 1700s, destroyed the Shaolin Temple and caused five fugitive monks to disperse throughout the land, thus creating a surrogate history for some of the other Shaolin temples and the spread of kung fu. Such stories are probably not true. Plenty of photographs of Shaolin Temple taken in the 1920s and earlier still exist, and show that the buildings were very old. Inscriptions can be seen in the photos documenting other parts of its long history of not being destroyed.

Nevertheless, there are times in its history when the Shaolin Temple was ransacked and even abandoned for periods of time, but it does not seem to have ever been destroyed prior to 1928.

Its original founding does indeed mark the probable start of both codified martial arts and Zen Buddhism in China, which is pretty remarkable. In the 5th century, an Indian Buddhist master named Buddhabhadra traveled to China to spread Buddhism, and by the year 477, he had become influential enough that Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei built the original Shaolin Temple for him to begin teaching Chinese monks. These are among the few facts of the early Shaolin that scholars generally agree upon.

Monks of all types had long practiced various forms of martial arts, particularly those closely associated with meditation, but it was during the decades surrounding the year 600 that the first true Shaolin methods began to be documented, now called the 18 arhat methods, and said to be based on the movements of five long-lived animals. Traditionally, but probably not factually, they are attributed to another visiting Indian Buddhist named Bodhidharma, who felt the monks needed stricter physical discipline to help with lengthy meditations. Virtually every ancient Shaolin tradition has such a fanciful tale attached to it.

Over the ensuing centuries, the Shaolin Temple performed basically the same function as it still did into the 20th century. It was essentially a boarding school for boys. The younger the recruit, the better; students as young as 5 or 6 years old were preferred. They developed tremendous flexibility and agility, and studied Buddhism. Ordinary students were called Secular Disciples, and once they reached young adulthood, most would go onto other things; but the few elite might become Martial Monks, the advanced level. Martial Monks, too, would eventually retire from the school and go onto other lives, but a few would make it a career.

After the Republican revolution, the Shaolin Temple was rebuilt, but operated modestly. In the ensuing decades, Mao's Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s and the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s marginalized the Shaolin Temple as it did other religious orders of all kinds throughout China. But then, after Chairman Mao's death, the Shaolin's golden modern era began, and became what we see today.

By the late 1970s the Temple was back in full business. It had been tremendously boosted by the Western publicity; young people from Europe and America clamored to train as Shaolin monks. The school of Secular Disciples was full of boys from mainly affluent Chinese families, and the Temple had to create a program for Foreign Disciples to accommodate the demand for martial arts tourism. And then, the Chinese government took notice.

The Shaolin Temple's value as a tourist attraction and a symbol of traditional China was clear. In 1980, the Chinese government hired a number of former masters to write new sacred Shaolin texts to replace those lost in 1928 (which is one reason there is so little reliability in modern texts on Shaolin history), and also to break ground on over 40 satellite schools. Today there are schools throughout China teaching these newly authored Shaolin methods, the largest of which accommodates over 8,000 students. The Shaolin were a symbol and a brand.

This new government-sponsored version of Shaolin was not blind to the value of sensationalism in marketing. And so something happened that should not surprise regular Skeptoid listeners. New abilities, some of them apparently superhuman, began to appear in the rewritten sacred texts. Suddenly the Shaolin martial artists were resisting spears thrust into their necks. They were standing on one finger. They were breaking bricks and sticks and stones with their heads. They were walking on fire and lying on beds of nails. They were resisting the most savage blows to every part of their anatomy, from punches, kicks, and sledgehammers. They were even doing all kinds of things with their testicles.

Without exception, all of these amazing feats are stage show tricks,

performed all around the world in many different cultures. Martial

artists call them bullshido.

There's no need to go into each of them here, if you're curious about

any of them — breaking the spear against the neck, for example —

Professor Google will show you how you can do it too.

Without exception, all of these amazing feats are stage show tricks,

performed all around the world in many different cultures. Martial

artists call them bullshido.

There's no need to go into each of them here, if you're curious about

any of them — breaking the spear against the neck, for example —

Professor Google will show you how you can do it too.

Today you'll find these Shaolin stage shows all over the world. If you've ever seen one, chances are it had no affiliation with the Shaolin Temple. Ever since the name Shaolin became a valuable brand, international promoters have been as quick to capitalize on it as were the Chinese, and it's currently trademarked in virtually every country. Nearly all of those trademarks were registered by businesspeople with no connection to the Shaolin. For more than a decade, the actual Shaolin Temple has been fighting legal battles and filing trademark complaints all over the world. The real Shaolin would love to give their own stage shows across Europe and the West; but in most countries they can't, because they'd be infringing on someone else's trademark. The battle they face is an uphill one. Many of these performing groups and martial arts academies were legitimately the first to conduct business in their country under the name, and in most countries, that's all that's needed to establish ownership of a trademark.

In 1972, when American TV viewers first saw Kwai Chang Caine wrap his arms around the hot cauldron and brand himself with the marks, what they didn't see was the rest of this elaborate test called the Wooden Men Labyrinth. But nobody else ever saw it either, because like so much of what we think we know of the Shaolin, it was the purely fictional invention of modern authors. Combined with the fake stage-show feats of indestructibility, this web of mythology woven around the reinvented Shaolin is most unfortunate. It takes away from what they really are. It's a school that teaches profound discipline and unmatched athleticism, in addition to its importance to the history of Zen Buddhism. Strip away the microwave noodle licensing and the bullshido, and let the Shaolin shine as the great symbol of traditional China they should be.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.