skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Putin’s Latest Problem Is Runaway Inflation

Putin’s Latest Problem Is Runaway Inflation

Even as price rises have moderated across much of the developed world, Russia’s struggles with price stability are getting worse.

As Russia fights the war in Ukraine, it is losing a battle at home—against inflation.

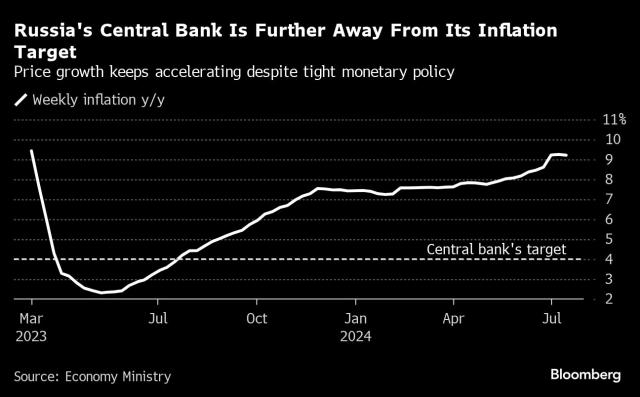

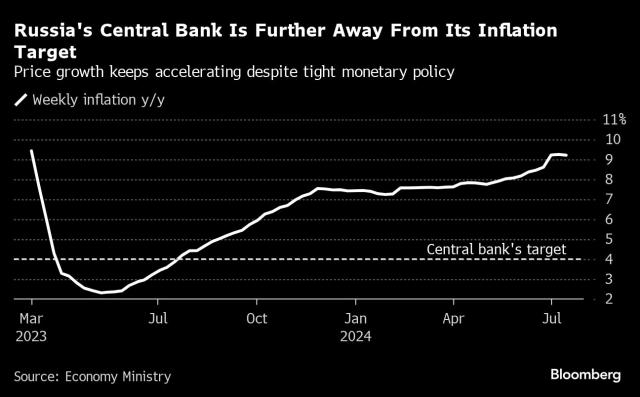

Last year, the Russian central bank more than doubled interest rates to tame prices. Inflation, though, kept rising, hitting over 9% this month, with a vast range of goods and services becoming costlier, from potatoes (up 91% so far this year) to economy-class flights (up 35%).

The central bank lifted its benchmark rate another 2 percentage points on Friday to 18%, making it one of the few central banks in the world to raise rates this year.

Inflation has become a hard-to-shake feature of Russia’s war economy. Even as price rises have moderated across much of the developed world, Russia’s struggles with price stability are getting worse.

A surge in military spending by the government and a record labor shortage, as working-age men go to the front or flee, have fueled wages and pushed up prices. Fresh rounds of U.S. sanctions, meanwhile, have complicated international payments, further driving up costs for importers.

A surge in military spending by the government and a record labor shortage, as working-age men go to the front or flee, have fueled wages and pushed up prices. Fresh rounds of U.S. sanctions, meanwhile, have complicated international payments, further driving up costs for importers.

Prices aren’t rising fast enough to cause an economic crisis or social unrest. But they are a sign of the growing imbalances under the hood of the economy. Stubborn inflation also means that prosecuting the war becomes costlier, which then leads to even larger military spending.

“In the inflation fight, Russian authorities have no good options—they can’t stop the war, they can’t solve the labor problem, they can’t stop raising wages for the population,” said Alexandra Prokopenko, a former Russian central-bank official who is now a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. “As long as the war goes on, inflation will remain high.”

“In the inflation fight, Russian authorities have no good options—they can’t stop the war, they can’t solve the labor problem, they can’t stop raising wages for the population,” said Alexandra Prokopenko, a former Russian central-bank official who is now a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. “As long as the war goes on, inflation will remain high.”

The Kremlin told reporters on Thursday that it is working on measures to contain prices as “certain inflationary processes are of concern to the government and the central bank.”

After suffering a recession following the start of the war, Russia’s economy rebounded as officials and businesses found ways to circumvent Western sanctions and sell oil abroad.

At the same time, a bigger transformation began to take hold.

The government reverted to Soviet-style military spending—equivalent to around 7% of gross domestic product—as the main driver of economic growth. Factories that churn out tanks, drones and soldiers’ clothing work in multiple shifts, seven days a week. That, in turn, has lifted wages and boosted prices.

In May, President Vladimir Putin replaced his longtime defense minister Sergei Shoigu with Andrei Belousov, a macroeconomist and an advocate for state intervention in the economy. That appointment, analysts say, was an acknowledgment that the economy and the war are now deeply intertwined.

The central bank had held its benchmark rate at a relatively high 16% since December, but it had little effect on prices. To tamp down out-of-control housing prices, authorities this month ended a popular mortgage subsidy that offered discounted rates as low as 8%, half the central bank rate. The program helped insulate Russians from the effects of the war but also fueled a property bubble.

Analysts at J.P. Morgan wrote in a recent report that the resilience of the Russian economy to tight monetary policy “remains a curious phenomena.”

“This clearly shows the limits of monetary policy in a situation of fiscal expansion and very tight labor markets,” said Vasily Astrov, an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies. “The central bank has little, if any, influence on fiscal policy and no influence at all on demography” he said, referring to the country’s shrinking population and labor force.

The central bank said in a recent report that reducing inflation will require a “significantly longer period” of higher interest rates than its earlier forecasts.

Borscht Index, a website whose cost-of-living gauge tracks the prices of beets, sour cream and other ingredients of the traditional hearty soup, reports a 26% increase compared with last year.

Among Russians, inflation evokes memories of the 1990s economic crisis during the painful transition to a market economy. Rising price tags have spurred some to cut consumption, limit vacations or band together in Telegram groups to discuss where to find the best deals.

The growing labor shortage is another major factor behind creeping inflation. Russia mobilizes as many as 30,000 soldiers every month while hundreds of thousands have fled to avoid being drafted.

Russia’s expanding military has eaten into the available labor force. Photo: Alexander Zemlianichenko/Associated Press

Russia’s demographic decline has exacerbated the lack of available labor, with officials reporting fewer high-school and university graduates. The number of migrants, a longstanding source of workers, has also dropped. That trend is likely to continue after authorities implemented stricter immigration controls in response to the March terrorist attack on the Crocus City Hall concert venue, which killed more than 140 people.

According to the central bank, businesses are missing both highly qualified experts and low-skilled workers.

The defense sector, despite pulling more than half a million workers from the civilian sector over the past year and a half, is short of about 160,000 specialists, Deputy Prime Minister Denis Manturov said last month.

Russian importers, meanwhile, have been smarting from U.S. sanctions imposed this year that raised the risk of secondary sanctions for foreign banks that deal with Russia. Chinese exports to Russia fell in recent months. Turkey’s trade with Russia has also stumbled under the pressure of sanctions this year.

“Usually Russia and its partners in the global South eventually find ways to circumvent sanctions,” Astrov said. “But it will be recurrent, because the U.S. will likely not stop there. In the end it is Russian consumers and businesses who will have to pay for this.”

A surge in military spending by the government and a record labor shortage, as working-age men go to the front or flee, have fueled wages and pushed up prices. Fresh rounds of U.S. sanctions, meanwhile, have complicated international payments, further driving up costs for importers.

A surge in military spending by the government and a record labor shortage, as working-age men go to the front or flee, have fueled wages and pushed up prices. Fresh rounds of U.S. sanctions, meanwhile, have complicated international payments, further driving up costs for importers. “In the inflation fight, Russian authorities have no good options—they can’t stop the war, they can’t solve the labor problem, they can’t stop raising wages for the population,” said Alexandra Prokopenko, a former Russian central-bank official who is now a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. “As long as the war goes on, inflation will remain high.”

“In the inflation fight, Russian authorities have no good options—they can’t stop the war, they can’t solve the labor problem, they can’t stop raising wages for the population,” said Alexandra Prokopenko, a former Russian central-bank official who is now a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. “As long as the war goes on, inflation will remain high.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.