I recently rose from a slumber to discover that many of

the learned had risen up to declare the U.S. war in Iraq not only a

failure but also a misbegotten undertaking that no person of minimal

intellect would have undertaken. There are two dangers in this view. The

first is that there is a class of warriors who went into harm’s way and

now carry the bitterness of the dead. The second is the bitterness of

those who didn’t go into battle yet held fragments of knowledge, enough

to mislead.

Obviously, all have a right to discourse, but judging anything as

complex as wars mere decades after they were fought risks

misunderstanding and rubbishing those who were there. The war’s veterans

can distort the facts too, but they are owed the benefit of the doubt

that they were not fools and that their memory carries with it a measure

of truth. I have children who fought in Iraq. They have the right to be

bitter if they choose. Those who judge a war whose real truth will not

be known for centuries – and even then it will be debated – are peering

into the dark.

Obviously, all have a right to discourse, but judging anything as

complex as wars mere decades after they were fought risks

misunderstanding and rubbishing those who were there. The war’s veterans

can distort the facts too, but they are owed the benefit of the doubt

that they were not fools and that their memory carries with it a measure

of truth. I have children who fought in Iraq. They have the right to be

bitter if they choose. Those who judge a war whose real truth will not

be known for centuries – and even then it will be debated – are peering

into the dark.

If these lines sound bitter, they are not meant to be. I wrote a book

as the war was intensifying, fully aware that my children would carry

the burden of casual thought. I want to begin by quoting from that book,

something always in bad taste but important to understand the necessity

of the war:

On the morning of September 11, 2001,

special operations units of the international jihadist group Al Qaeda

struck the United States. In a classic opening attack, they struck

simultaneously at the political, military, and financial centers of the

United States. The attack on the political centers failed entirely when

the aircraft assigned to that mission crashed prematurely in

Pennsylvania. The attack on the military center was only partially

successful. The aircraft assigned to that target crashed into a section

of the Pentagon that had been modernized with fire-resistant materials,

which effectively contained the explosion. The planes assigned to attack

the U.S. financial center succeeded completely, not only destroying the

World Trade Center towers but closing down the financial markets for

several days and disrupting the U.S. economy.

The nineteen men who carried out the

mission were capable operatives. Their achievement was not taking

control of four airliners simultaneously, although that was not a

trivial accomplishment. Rather, it was planning, training, and deploying

for the operation without ever being detected by American intelligence –

or, more precisely, acting in such a way that in spite of inevitable

detection, the data never congealed into actionable intelligence. While

their military capabilities were enormously inferior to those of the

United States – they had to steal an air force – their skills at covert

operations were superb.

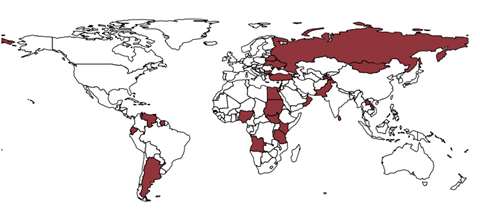

A major asset of al-Qaida was that it possessed a highly dispersed

force that enabled it to group and regroup. It had demonstrated the

ability to operate globally while maintaining political relations in a

fixed position. Al-Qaida had political operations in Saudi Arabia,

Pakistan, Afghanistan and as far east as Southeast Asia. It operated

throughout these areas, growing its regional influence and maintaining a

capability to operate widely. The attack on the United States

demonstrated the ability to operate in many environments. Most

important, al-Qaida could disperse while maintaining offensive power.

Al-Qaida therefore posed multiple threats in multiple regions. It

could strike covertly as in the United States while maintaining regional

bonds in Afghanistan and exploring the Pacific. Its force was so highly

dispersed that its ability to strike would outrun even U.S.

intelligence, which was focused on operational threats. Al-Qaida was

focused on maintaining a wide range of options without providing

relations and resources that could be neutralized. It was precisely this

capability that enabled al-Qaida to operate covertly in the United

States and kill 3,000 people without putting the group’s core at risk.

Al-Qaida therefore posed multiple threats in multiple regions. It

could strike covertly as in the United States while maintaining regional

bonds in Afghanistan and exploring the Pacific. Its force was so highly

dispersed that its ability to strike would outrun even U.S.

intelligence, which was focused on operational threats. Al-Qaida was

focused on maintaining a wide range of options without providing

relations and resources that could be neutralized. It was precisely this

capability that enabled al-Qaida to operate covertly in the United

States and kill 3,000 people without putting the group’s core at risk.

This was a force that could not be rapidly defeated. Nor could it be

negotiated with or even located for negotiations. There was no political

option or opportunity to divide the force. And the possibility to

penetrate it was an illusion.

At the same time, the United States could not accept the status quo.

Al-Qaida had demonstrated its capabilities, and there was no reason it

would not strike again. Lacking political solutions, Washington’s only

option was a military strike – a broad and diffuse campaign designed to

fragment al-Qaida. That meant U.S. operations on a nearly global basis,

from Saudi Arabia to Myanmar.

This could not be a conventional war for three reasons. First, the

enemy had no center of gravity. Second, the attacking force had to

disperse. Third, the normal logic of intelligence did not apply.

Following 9/11 with meticulously targeted attacks against al-Qaida was

not an option, as the intelligence did not exist. Al-Qaida was hidden

even within the United States, had no center, and was seen as relentless

in its hostility and ability to strike.

This could not be a conventional war for three reasons. First, the

enemy had no center of gravity. Second, the attacking force had to

disperse. Third, the normal logic of intelligence did not apply.

Following 9/11 with meticulously targeted attacks against al-Qaida was

not an option, as the intelligence did not exist. Al-Qaida was hidden

even within the United States, had no center, and was seen as relentless

in its hostility and ability to strike.

Invading Afghanistan and Iraq was the only practical option if the

goal was to cripple a very capable enemy. The U.S. launched broad

attacks in multiple countries. This could provoke hostility, but there

was no better option. It was an unconventional counteroffensive, and

this is what its critics dislike, but they offer no clear alternative.

After 9/11, the threat was simply too great. The strategy was worldwide

disruption. It was not pretty, but it worked. There were no other

large-scale attacks on the U.S. homeland.

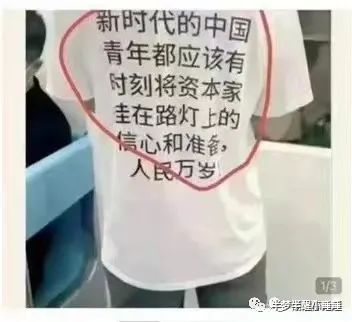

暗示北京可能进行报复