Coming War Between the US and Venezuela

It isn’t just a bilateral affair.

Allison Fedirka -

Last week, two seemingly independent events – the declaration of a state of emergency by the government in Bogota and the United States’ planned review of Chevron’s license to operate in Venezuela – suggest a confrontation between Washington and Caracas is in the offing.

It’s no secret that the United States’ physical and economic security depends on the security of the Western Hemisphere, and it’s no secret that Washington has been rethinking how it engages the region. Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. has taken a comparatively hands-off approach. In fact, Western Hemispheric affairs – save for Mexico and Canada – tend to take a back seat to European, Russian and Asian affairs. But threats such as the ones Venezuela is believed to pose have persuaded Washington to be more interventionist. The threats, in Washington’s estimation, are three-fold. First, corruption and economic decline under the Maduro regime made Venezuela ripe for illicit criminal activities such as drug trafficking, gun running and illegal mining, compelling many Venezuelans to flee the country for better conditions. Second, an influx of irregular migration has occurred as a result. Third, the Maduro government aligned itself with China, Russia and Iran, offering a foothold in the Americas in exchange for political and economic support.

This helps to explain why some of President Donald Trump’s first actions in office hit close to home. In the hours after assuming office, he said the U.S. no longer needed Venezuelan oil, and so the U.S. could soon stop buying it. He also signed an executive order that repealed the CHNV (Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela) humanitarian parole program, which allowed as many as 30,000 Venezuelans to enter the U.S. legally per month and stay up to two years. And, through Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the U.S. government officially recognized Venezuelan opposition leader Edmundo Gonzalez as the democratically elected president of the country. U.S. special envoy for Venezuela, Richard Grenell, has already spoken with officials from the Maduro and Gonzalez camps.

The bottom line is that the U.S. wants regime change, and the most telling sign toward that end was Rubio’s suggestion to review U.S. policies toward Chevron. Chevron received a special license to resume oil production and exports through its joint venture with Venezuela’s state-run oil company, PDVSA. The license meant to achieve two goals: provide a positive incentive for free and fair elections, and enable Chevron to make good on debt payments without contributing taxes or royalties to the Venezuelan government. (The company hoped to recover $750 million in unpaid debts and dividends by the end of 2024 and the remainder of the outstanding $3 billion by the end of this year.) It failed in its first goal, which ultimately gave Rubio cause to say Caracas neglected to hold up its end of the bargain.

The revocation of Chevron’s license allows the U.S. to target Venezuela’s oil industry and undermine the regime without much backlash. It would simultaneously reduce U.S. imports from Venezuela and Venezuelan oil production – the economic impact of which would be felt much more heavily in Caracas than in Washington. Though Venezuela supplies the U.S. with a type of heavy crude that has limited alternative suppliers (namely Mexico, Colombia and Ecuador), its total share of U.S. imports of crude oil and related products was a mere 1.5 percent. Commodity analysts estimate that removing Chevron from the equation would result in production declines of up to 830,000 barrels per day this year. In theory, Venezuela could replace Chevron with a different operator, but even if it did, it would still struggle to find buyers. Russia’s Rosneft has little appetite for further Venezuelan investments; China National Petroleum Corp. has become less bullish on Venezuela; and the U.S.-based North American Blue Energy Partners’ Venezuela branch has a dubious business record (including accusations of non-payment for services rendered). Crucially, the removal of Chevron’s license does not involve any military action, which would jeopardize U.S. relations throughout the entire hemisphere.

There’s little Venezuela can do about any of this, at least directly, so as a strategic response it will likely turn to proxy groups like Colombia’s National Liberation Army (or ELN). The Maduro regime is known to support black market activities as a means to generate additional revenue and resources. One of the most important figures in this enterprise is Diosdado Cabello, who controls the country’s military, national guard and intelligence apparatus. Under his watch, the military has allowed soldiers to participate in or oversee black market activities to earn their loyalty and supplement their income. Venezuelan security bodies have close ties to organized crime groups, allowing them to cross borders for trade, find a haven in Venezuela and conduct illegal activities in exchange for financial compensation. The ELN has benefited from this arrangement. It now boasts a strong presence in both Colombia and Venezuela and has amassed substantial financial resources through illegal mining, drug trafficking, extortion and contraband.

This helps to explain why some of President Donald

Trump’s first actions in office hit close to home. In the hours after

assuming office, he said the U.S. no longer needed Venezuelan oil, and

so the U.S. could soon stop buying it. He also signed an executive order

that repealed the CHNV (Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela)

humanitarian parole program, which allowed as many as 30,000 Venezuelans

to enter the U.S. legally per month and stay up to two years. And,

through Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the U.S. government officially

recognized Venezuelan opposition leader Edmundo Gonzalez as the

democratically elected president of the country. U.S. special envoy for

Venezuela, Richard Grenell, has already spoken with officials from the

Maduro and Gonzalez camps.

The bottom line is that the U.S. wants

regime change, and the most telling sign toward that end was Rubio’s

suggestion to review U.S. policies toward Chevron. Chevron received a

special license to resume oil production and exports through its joint

venture with Venezuela’s state-run oil company, PDVSA. The license meant

to achieve two goals: provide a positive incentive for free and fair

elections, and enable Chevron to make good on debt payments without

contributing taxes or royalties to the Venezuelan government. (The

company hoped to recover $750 million in unpaid debts and dividends by

the end of 2024 and the remainder of the outstanding $3 billion by the

end of this year.) It failed in its first goal, which ultimately gave

Rubio cause to say Caracas neglected to hold up its end of the bargain.

ELN and Other Guerrilla Presence in Colombia and Venezuela

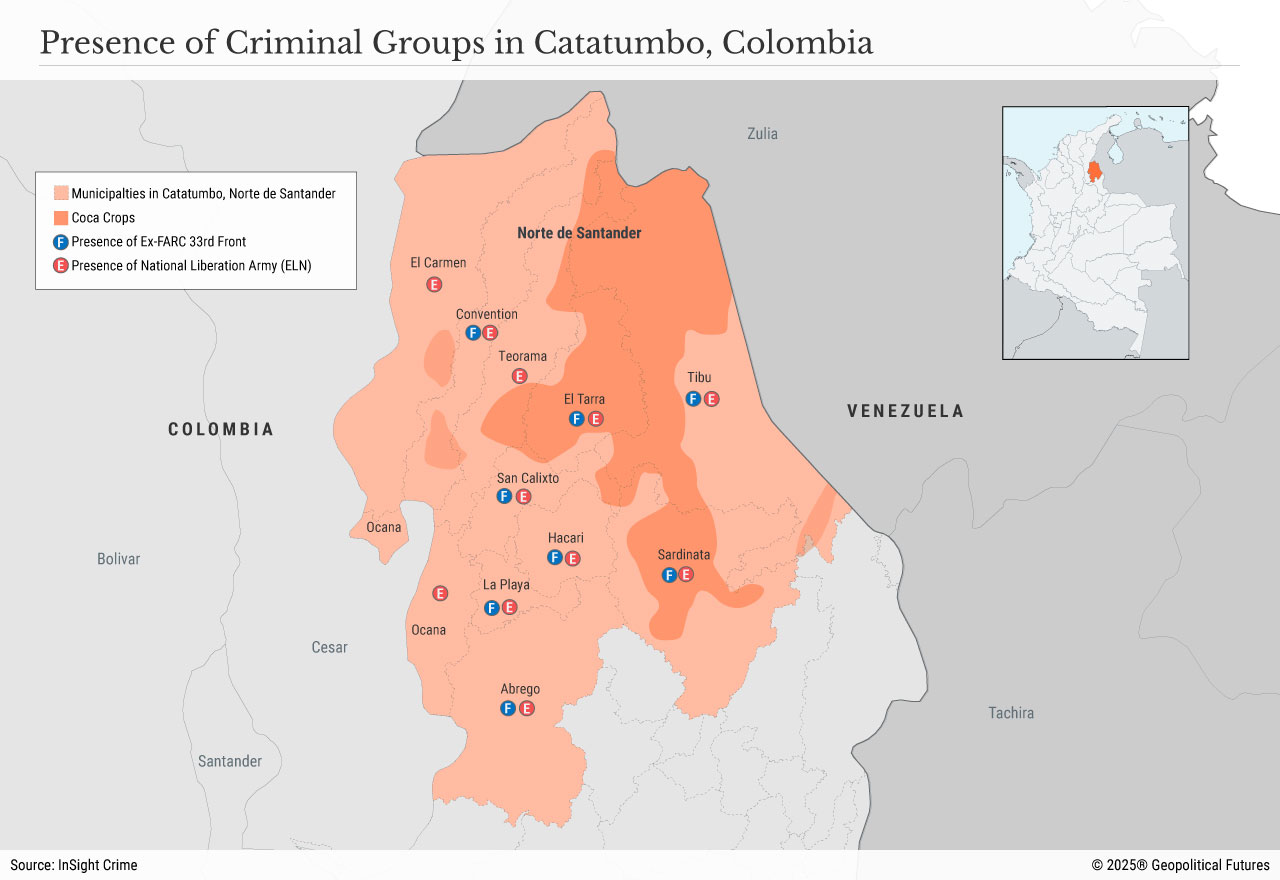

Through its ties with the ELN, Venezuela can pressure the Colombian government and create problems for the U.S. It’s likely no coincidence that the recent ELN attacks in Colombia’s Catatumbo province came as Washington intensified its rhetoric against Venezuela. In fact, the impetus behind the attacks goes back to November, when, shortly after the U.S. presidential election, a major cocaine shipment went missing. (Rumors swirled that the shipment was linked to the regime.) The incident triggered a split between the ELN and the former FARC’s 33rd Front in Catatumbo. A more recent bout of fighting occurred days after the administration of Colombian President Gustavo Petro broke off peace talks with the ELN, accusing the group of trying to control coca-producing areas. The fighting was bad enough for the Colombian government to declare a state of emergency in the province. Presence of Criminal Groups in Catatumbo, Colombia

Presence of Criminal Groups in Catatumbo, Colombia

This string of events served Maduro’s interests. The violence helped justify the execution of Venezuela’s Bolivarian Shield military exercises. These drills, which started Jan. 22 and included the deployment of some 2,000 additional troops to the border, allow Venezuela to posture directly against Colombia and to provide support for ELN fighters against rival groups. And while most Colombians impacted by the ELN fighting fled to other parts of the country, about 1,000 opted to escape to Venezuela, giving Caracas the political opportunity to provide humanitarian assistance to those who could not get it in Colombia.

For Colombia, the consequences are many. For one thing, it is beyond doubt that Venezuela can create instability inside its borders. After the violence in Catatumbo, the interior minister admitted that the government would be unable to achieve its “Total Peace” initiative – a damning blow to the administration. The ELN’s ties to Caracas protect the group from Colombian military reprisal. And the whole episode came as Washington issued a 90-day suspension of international aid along with U.S. pledges to enact tariffs and sanctions against Colombia for turning away two aircraft carrying deportees from the United States.

From these events come a few key takeaways. First, Maduro seems to be trying to recover properties and facilities used by drug traffickers. Second, Maduro has, to some degree or another, an auxiliary group in the ELN that can bolster his security forces and create problems when needed. Third, Colombia – the country on which the U.S. relies for inroads into Venezuela – is increasingly bearing the burden of irregular Venezuelan migration. Last, a relationship between the ELN and the Maduro regime makes talks between Caracas and Washington practically impossible. Cabello is a pivotal figure in the relationship between the ELN and the Maduro regime, and his past role in abuse, money laundering and drug trafficking means he cannot be included in any political deals that give leaders amnesty for stepping down. This means there is a strong force inside the Venezuelan government that can block attempts at political dialogue and resolution.

It’s clear a showdown between the U.S. and the Maduro regime will play out soon. It just won’t play out bilaterally.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.