How Hong Kong protects people from dangerous landslides

Faced with the prospect of worsening landslides due to climate change, Hong Kong is working to produce ever more accurate warnings of the danger

"It happened as quick as lightning, but it only took seconds to create so much destruction."

Michael Lau, now 63, speaks with a slight tremor as he describes how he witnessed one of the most deadly landslides to occur in Hong Kong in the past 50 years.

On a warm day back in June 1972, a then 13-year-old Lau, who lived on the second floor of a public housing estate in the Sau Mau Ping neighbourhood, was unable to play his usual table tennis outside with friends due to the heavy rain.

"Instead, I went out on the balcony where we lived," he recalls. "All of a sudden, opposite to me, I saw rooftops flying around as the landslide was coming down the nearby hill. Houses were sliding down the slope together with the mud."

Lau was speechless with shock. "I just remember seeing people's hands rising out of the mud. They were covered in blood. They raised their hands because they wanted people to help them. There were cars floating along in the landslide too. People were trying to dig them out."

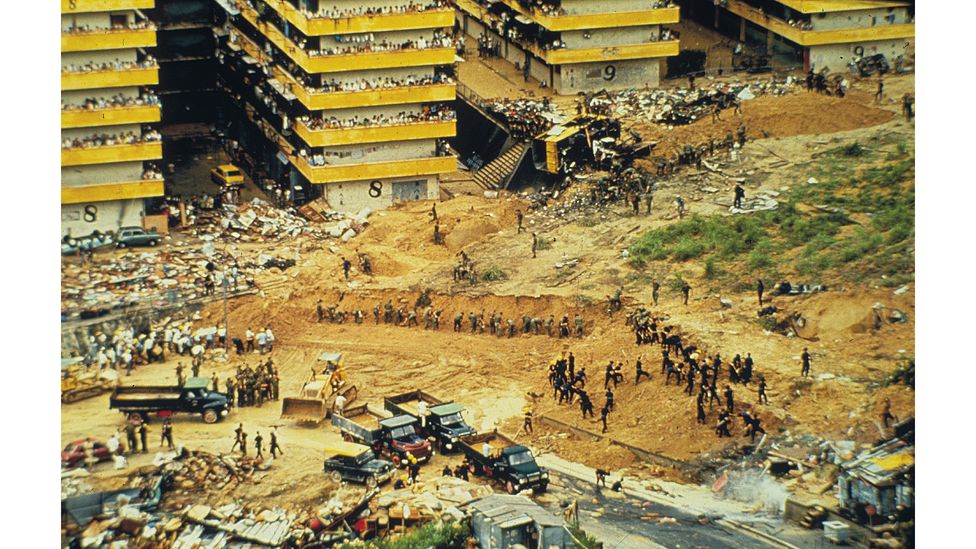

In total, 71 people were killed by the landslide that day, including many children. Lau and his family survived, but many people he knew were not as fortunate. "All the friends that I used to play table tennis with were all killed in the landslide," says Lau. Today the disaster site is home to the Sau Mau Ping Memorial Park, a collection of benches at the foot of a hillside surrounded by nearby high-rise housing estates.

The 1972 Sau Mau Ping landslide in Hong Kong killed 71 people (Credit: Hong Kong Government)

Between the 1950s and 1970s, Hong Kong experienced rapid economic growth and its population almost doubled. Many people lived in houses and squatter huts built on steep hillsides. This combination of urban development and the city's hilly terrain led to a high risk from landslides. But warnings for landslides didn't exist, and a number of severe and catastrophic landslides in the 1970s resulted in great loss of life and damage to properties.

1972 was a particularly deadly year, with 156 people killed. Two of the city's most deadly landslides, Sau Mau Ping and Po Shan Road, occurred on the same day, killing 138 people in total. Most landslides in Hong Kong kill far fewer people, but it still experienced a number of similar tragic incidents over the years, with more than 400 landslide fatalities between 1947 and 2008.

We will never know exactly how many lives we have saved because those casualties didn't happen – Lawrence Shum Ka Wah

However, since the 1970s, the city has been pioneering in its approach to landslide risk mitigation. It was the first to design and operate a territorial landslide early warning system, introduced in 1977 to alert the city of when there was a high probability of rainfall-induced slope failures. Deaths from landslides have dropped substantially since the mid 1980s, and Hong Kong has not seen a single landslide fatality since 2008. The system has since inspired other landslide early warning systems around the world, including in Brazil, San Francisco, Norway and Japan, says Luca Piciullo, a researcher at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute.

Hong Kong has still not eliminated its landslide risk though, and now faces the prospect of increasingly intense rainfall due to climate change. Scientists say more intense rainfall, will likely lead to increased landslides across the globe, especially in mountainous areas with snow and ice. But Hong Kong's engineers are continuing to innovate, and now plan to use artificial intelligence to design one of the world's most advanced landslide early warning systems.

A landslide occurs when the stability of a slope is disturbed by heavy rainfall, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or even human activity, leading rock, debris or mud to fall down the slope. They can occur anywhere in the world, and are the most common type of geological event. Landslides affected an estimated 4.8 million people and caused more than 18,000 deaths between 1998 and 2017.

Hong Kong is particularly vulnerable to landslides because of its hilly topographical setting – 60% of land in the city is mountainous – and very dense population. Most landslides here occur during or after rainstorms, with an average 300 landslides every year in the city.

Hong Kong has done much to reduce the risk of landslides, including through mitigation works in Tung Chung, Lantau Island (Credit: K.Cheng/SCMP/Getty)

Providing resilience has been no easy task. But the deadly landslides of 1972 triggered the establishment of Hong Kong's Geotechnical Engineering Office (GEO), still one of the most active government-led landslide risk reduction and slope safety systems globally.

The GEO's approach to reducing the risk of landslides in the 1970s was "innovative and pioneering", says Piciullo. At the time, a focus on structural slope stabilisation was the most widely used approach to reduce landslide risk, he says. Hong Kong's approach was very different: it focused on alerting city officials, first responders and the population of the high probability of rainfall-induced slope failures, in effect setting up the world's first regional landslide warning system.

For more than 40 years, one of its most successful programmes has been the landslip warning system. The warning is raised during heavy periods of rainfall to alert the public of potential landslide danger and broadcast across radio and TV news stations at regular intervals, together with advice on precautionary measures the public should take, such as keeping away from steep slopes and cancelling non-essential appointments. Motorists are advised to avoid driving in hilly areas or on roads with landslip warning signals

The emergency control centre at Hong Kong's Geotechnical Engineering Office (Credit: GEO/Hong Kong Government)

The GEO combines several data sources to decide on whether to issue the warning. Real-time rainfall data is gathered by a network of rain gauges installed across the city, while rainfall for the coming few hours is forecast by the Hong Kong Observatory. These are compared with data showing the correlation between past recent rainstorms and landslides to determine the need for the warning.

"We have statistics showing that 90% of landslide fatalities occurred when the landslip warning was in force," says Lawrence Shum Ka Wah, chief geotechnical engineer at the GEO. "Landslides only come from slopes. If people stay away from slopes, there will be no casualties. So early warning is very important."

The landslip warning system has been "a lifesaver" by reducing landslide fatalities, says Wah. "We will never know exactly how many lives we have saved because those casualties didn't happen."

People might not have seen a landslide for a long time and they stop caring about it – Michelle Yik

Geotechnical engineers in Hong Kong have also done much to reduce the risk of landslides happening in the first place. They now understand better how slopes fail, have compiled a comprehensive slope catalogue with information on 60,000 man-made slopes, covering their geometry, geology and formation history. They have also upgraded thousands of older slopes to meet modern safety standards.

To better alert public about potential landslide danger, in 2005 the GEO also introduced the landslide potential index, a statistical model used to warn when there is the highest potential for fatal and severe landslide incidents.

Unlike the landslip warning, which is issued ahead of rainstorms, the landslide potential index estimates the risk of landslides directly after major rainstorms have ended. It uses the city's network of more than 120 automatic rain gauges to measure the intensity and location of the rainfall, and combines this with analysis of historical landslide records and the distribution of slopes to predict how many landslides could occur.

The GEO in Kong Hong is among the world's most active landslide risk reduction and slope safety systems (Credit: GEO/Hong Kong Government)

The last fatalities caused by a landslide in the city occured in 2008, when a heavy rainstorm battered Hong Kong's outlying Lantau Island, resulting in more than 2,400 natural terrain landslides and two deaths. Hong Kong still sees hundreds of landslides per year, although most are minor ones on roadsides in remote hillside areas.

But GEO's success with slope safety may have made many people in Hong Kong think they are immune to the dangers of landslides, says Michelle Yik, a psychologist at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. "People might not have seen a landslide for a long time and they stop caring about it."

Better education and larger awareness among the public about the risks of landslides is still needed, agrees Wah. Since 2019, the index has begun to classify severe rainstorms into three categories: "high", "very high" and "extremely high" risk. Applying the same method to past rainstorms shows that fatalities have occurred in every rainstorm that has reached the "extremely high" category. There have been three such rainstorms since records began in 1984.

If a severe rainstorm like the one in 2008 that battered Lantau Island was to happen today in Hong Kong Island or Kowloon we would not be prepared – Charles WW Ng

"The landslide potential index is a relatively simple, in concept at least, and extremely functional system for determining typical risk levels," says Stuart Mills, associate director of infrastructure at enginerring multinational Arup. Hong Kong's hugely comprehensive inventories of landslide occurrence has allowed it to establish statistically reliable relationships between rainfall intensity and landslide occurrence, he says. This has in turn enabled it to establish threshold levels above which landslide risks become more pronounced.

"The ability to correlate these relationships with real-time rainfall intensity data has provided us with a powerful tool for landslide risk management and disaster preparedness."

A rescue worker looks for survivors after a mudslide in Petropolis, Brazil in February 2022. (Credit: C.SOUZA/Getty)

But there is still a huge need to improve visibility of the index among the public. Yik says a (not yet published) survey she conducted of people living in areas of Hong Kong prone to landslides found only 10% of the 1,834 people interviewed had even heard of the landslide potential index.

The current two systems are also more geared towards the consequences of landslides than overall risks, says Charles WW Ng, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Both are posted either during or after a rainstorm has occurred to warn people of the risks, but don't try to actually prevent these risks. A risk-based system, meanwhile, would try to minimise the landslide before it happens.

"Even if we loosely say we are ready for a once-in-500-year rainfall, it doesn't mean that a once-in-a-1,000-year rainfall couldn't fall tomorrow," says Ng. "So the risk is always there. […] We should try our best to reduce the risk and not just wait for it to happen and then deal with the consequences."

While most landslides in Hong Kong are small these days, the city is also not ready for the more severe rainfalls expected to come with climate change, adds Ng. "If a severe rainstorm like the one in 2008 that battered Lantau Island was to happen today in Hong Kong Island or Kowloon we would not be prepared," says Ng. The damage to infrastructure and potential loss of life would be "unimaginable".

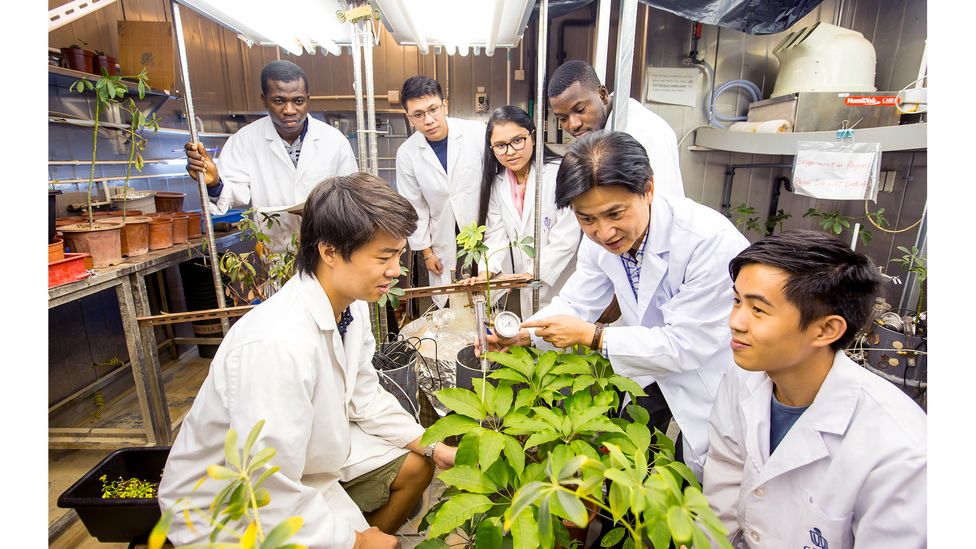

Charles WW Ng (second from right) and his team are developing a new "risk-based" landslide early warning system for Hong Kong, which they hope to introduce by 2024 (Credit: HKUST)

Ng is leading a team developing a new extreme weather and landslide early warning system, which it hopes to introduce by 2024. The new system aims to increase the forecast lead time from three to six hours, by using artificial intelligence and machine learning technology to study which rainfall patterns most seriously affect Hong Kong, and where these occur. "A three-hour difference can make a big difference in terms of saving human lives," says Ng. "Ultimately, we hope we will be able to predict rainfall patterns more accurately at a regional level.".

The current warning system tells people to stay home if rainfall reaches 70mm (2.8in), but does not advise them on other actions, such as how far they need to move away from hill slopes. The new app will try to deliver more detailed practical advice, including via an app which sends people early warnings.

Once complete, the new system will set a benchmark internationally, says Ng. Other experts say the new system will yield valuable findings. "It's a fabulous opportunity to take what is already world-leading experience and knowledge even further and keep Hong Kong practitioners at the very forefront of landslide risk management," says Mills.

I have witnessed how everything can change in just a matter of seconds – Michael Lau

Ng says the system could also be used in other landslide prone regions such as Brazil, Italy, Japan, India and Thailand. "Currently many cities situated in mountainous regions […] are not prepared for the potentially devastating impact of unprecedented extreme rainstorms due to climate change."

There are already more than 24 landslide early warning systems operational worldwide, concentrated in the US, South East Asia, East Asia and Italy. But while they are gaining increased attention, many areas with high landslide risk still lack them.

An indigenous woman and child walk by a landslide that destroyed the Guatemalan village of Queca after heavy rains from a hurricane in 2021 (Credit: J.ORDONEZ/Getty)

In the last decade, some developing countries have set up community-based systems, says Piciullo, which are perceived as a cost-effective landslide risk mitigation measure due to their relatively simple monitoring networks. Such systems in places like Chittagong in Bangladesh and the favelas of Rio de Janeiro directly warn the population of the possible occurrence of landslides during heavy rainfall and to invite them to move to safer places. As in Hong Kong, the interaction of technical and social aspects is paramount in these systems, notes Piciullo. "Often people in the communities, specifically the ones living in areas that have not experienced landslides, do not move to safe places if warnings are issued or sirens activated."

While not all countries will be able to afford Hong Kong's intricate technical equipment, the team behind the city's new system say they are willing to share their knowledge with other countries. "We are working with a professor in mainland China to help countries along the Belt and Road that are similar in geography to Hong Kong, very hilly and also subject to heavy rainfall," says Ng. "When we publish the papers all countries can borrow our findings and modify them to suit their local needs. They can also collaborate with us."

Michael Lau experienced the devastating Sau Mau Ping as a child in 1972. Now 63, he visits the Sau Mau Ping Memorial Park (Credit: M.Keegan)

Neither rainfall forecast nor landslide prediction will ever be an exact science. "We always tell the public that landslide risk is never zero," says Wah. "A once-in-a-thousand-year rainstorm will hit Hong Kong one day."

However, Hong Kong's action on landslides has made residents feel a lot more secure, including Lau, who witnessed the tragic 1972 Sau Mau Ping landslide.

"Today I do feel more safe living here," he says. "The government has put slope safety measures in place like barriers and reinforcements to make sure the area is safer. They have strengthened the infrastructure and I don't feel at risk."

He says the landslip warning signal is clear and always alerts him to the danger. "I'm aware of the index as well," he says. "The surroundings hills are filled with water after rainstorms and so there is a risk that another landslip could happen."

But Lau is also aware that landslide risk can never be reduced to zero, something which makes him philosophical in his approach to daily life. "I have witnessed how everything can change in just a matter of seconds. Everything can change as quick as lightning," he says. "So I try to just make the most of every day."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.