The Nazi Inspiring China’s Communists

A decades-old legal argument used by Hitler has found support in Beijing.

When Hong Kong erupted into protest this summer against a national-security law imposed by Beijing, the fact that Chinese scholars leaped to the Communist Party’s defense was perhaps predictable. How they argued in favor of it, however, was not.

“Since Hong Kong’s handover,” Wang Zhenmin, a law professor at Tsinghua University, one of China’s most prestigious institutions, wrote in People’s Daily, “numerous incidents have posed serious threats to Hong Kong’s prosperity and stability.” The city, Wang was effectively arguing, was in no position to discuss civil liberties when its basic survival was on the line. Qi Pengfei, a specialist on Hong Kong at Renmin University, echoed those sentiments, insisting that the security law was meant to protect the island from the “infiltration of foreign forces.” In articles, interviews, and news conferences throughout the summer, scores of academics made a similar case.

Though Chinese academics are often circumscribed in what they can and cannot say, they nevertheless do disagree in public. At times, they even offer limited, and careful, critiques of China’s leadership. This time, however, the sheer volume of pieces that Chinese scholars produced, as well as the nature of those arguments—consistent, coordinated, and often couched in sophisticated legal jargon—suggested a new level of cohesion in Beijing on the acceptable scope of the state’s power.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has markedly shifted the ideological center of gravity within the Communist Party. The limited tolerance China had toward dissent has all but dissipated, while ostensibly autonomous regions (geographically as well as culturally), including Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Hong Kong, have seen their freedoms curtailed. All the while, a new group of scholars has been in ascendance. Known as “statists,” these academics subscribe to an expansive view of state authority, one even broader than their establishment counterparts. Only with a heavy hand, they believe, can a nation secure the stability required to protect liberty and prosperity. As a 2012 article in Utopia, a Chinese online forum for statist ideas, once put it, “Stability overrides all else.”

Prioritizing order to this degree is anathema to much of the West, yet perspectives such as these are not unprecedented in Western history. In fact, China’s new statists have much in common with a faction that swept through Germany in the early 20th century.

That affinity is no accident.

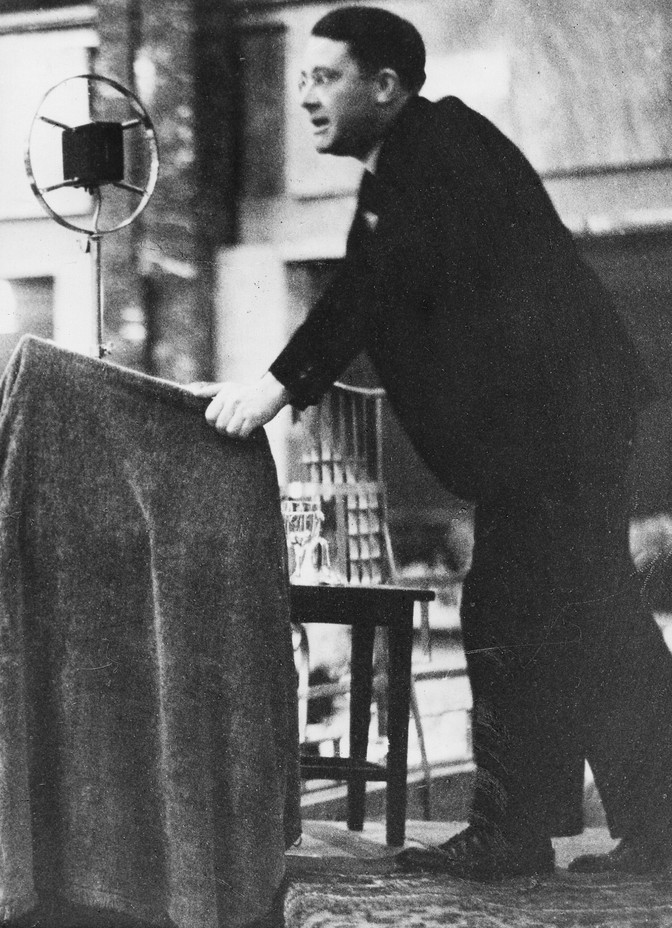

China has in recent years witnessed a surge of interest in the work of the German legal theorist Carl Schmitt. Known as Hitler’s “Crown Jurist,” Schmitt joined the National Socialist Party in 1933, and, though he was only officially a Nazi Party member for three years, his anti-liberal jurisprudence had a lasting impact—at the time, by helping to justify Hitler’s extrajudicial killings of Jews and political opponents, and then long afterward. Whereas liberal scholars view the rule of law as the final authority on value conflicts, Schmitt believed that the sovereign should always have the final say. Commitments to the rule for law would only undercut a community’s decision-making power, and “deprive state and politics of their specific meaning.” Such a hamstrung state, according to Schmitt, could not protect its own citizens from external enemies.

Schmitt’s influence is most evident when it comes to Beijing’s policy toward Hong Kong. Since its handover to China from Britain in 1997, the city has ostensibly been ruled under a “one country, two systems” framework, whereby it would be part of China, but its freedoms, independent judiciary, and other forms of autonomy would be preserved for 50 years. Over time, these freedoms have been eroded as the CCP has sought greater control, and more recently have been undermined completely with the national-security law.

Chen, who has written extensively on Hong Kong policy since 2014 and, according to The New York Times, is a former adviser to Beijing on the issue, cited Schmitt directly in defense of the concept of a national-security law back in 2018. “The German jurist Carl Schmitt,” he argued in an article, distinguishes between state norms and constitutional norms. “When the state is in dire peril,” Chen wrote, citing Schmitt, state leaders have the right to suspend constitutional norms, “especially provisions for civil rights.” Jiang Shigong, also a law professor at Peking University, has made a similar case. Jiang, who worked as a researcher in Beijing’s Liaison Office in Hong Kong from 2004 to 2008, employs Schmitt’s ideas extensively in his 2010 book, China’s Hong Kong, to resolve tensions between sovereignty and the rule of law in favor of the Communist Party.

Jiang is also widely credited with authoring the 2014 Chinese-government white paper that gives Beijing “comprehensive jurisdiction” over Hong Kong. In a nod to Schmitt, the paper claims that the preservation of sovereignty—of “one country”—must take precedence over civil liberties—of “two systems.” Using Schmitt’s rationale, he raises the stakes of inaction in Hong Kong insurmountably high: No longer a liberal transgression, the security law becomes an existential necessity.

Chen and Jiang are “the most concrete expression thus far of [China’s] post-1990s turn to Schmittian ideas,” Ryan Mitchell, a law professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, wrote in a paper in July. They are the vanguard of the statist movement, which supplies the rationale for the authoritarian impulses of China’s leaders. And though it is unclear precisely how powerful they are in the upper echelons of the party, these statists share the same outlook as their paramount leader. “Xi Jinping’s big project is on reinventing and revitalizing state capacity,” Jude Blanchette, China chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me. “He is a statist.”

Why has a Nazi thinker garnered such a lively reception in China? To some degree, it is a matter of convenience. “Schmitt serves certain purposes that Marxism should have done, but can no longer do,” Haig Patapan, a politics professor at Griffith University in Australia who has written on Schmitt’s reception in China, told me. Schmitt gives pro-Beijing scholars an opportunity to anchor the party’s legitimacy on more primal forces—nationalism and external enemies—rather than the timeworn notion of class struggle.

Ideology is only part of the story, though. Another explanation is found in China’s history. In the 1930s, the country’s then-leader Chiang Kai-Shek developed a deep admiration for Nazi Germany. “[Germany] was a country like China that had unified itself late,” William Kirby, a professor of China studies at Harvard University and the author of Germany and Republican China, told me. For China, a nation flanked by foreign adversaries, the German example of rapid modernization seemed exemplary. In 1927, Chiang would hire the German artillery expert Max Bauer to be his military adviser; his own son, Chiang Wei-Kuo, would serve in the Wehrmacht, the Nazi military arm, during the 1938 invasion of Austria.

One lesson from Chiang’s rule is that threats from abroad can stoke authoritarianism at home. And for almost a century, even as power transferred from Chiang’s Nationalists to Mao Zedong’s Communists, fear of “enemy” infiltration—the seedbed for fascism—lingered in China’s national psyche. “Who are our enemies? Who are our friends?” Mao asked in the very first line of his Selected Works. Later, from 1989 to 1991, 500 articles in the People’s Daily, the state-controlled paper, contained the phrase “hostile forces.” The perceived threat of invasion, or at minimum suspicion of outsiders, continues to inform contemporary politics. Such anxiety lends credence to the anti-liberal theories of Carl Schmitt, who once proclaimed that all “political actions and motives can be reduced [to that distinction] between friends and enemies.”

The pandemic has further ensconced statists’ views. That China has gotten rid of the virus, which President Donald Trump called “the invisible enemy,” while the United States remains hobbled by it, is portrayed among Chinese statists as a triumph for the Schmittian worldview.

“Since Xi Jinping became China’s top leader,” Flora Sapio, a sinologist at the University of Naples, wrote, “Carl Schmitt’s philosophy has found even wider applications in China, in both ‘Party theory’ and academic life.” This shift is significant: It marks a move from what had been an illiberal government in Beijing—one that flouts liberal norms as a matter of convenience—to an anti-liberal government—one that repudiates liberal norms as a matter of principle.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.