关税只是拼图的一块 特朗普雄心勃勃的经济计划和对手的策略

4月2日,美国总统特朗普宣布对外国商品征收激进的新关税,并强调这一天是美国的“解放日”。随后,全球经济根基迎来动荡的一周,一个新经济时代被宣告到来。

事实上,特朗普正在兑现他的竞选承诺。他曾向全球大公司和制造商喊话,“如果你不在美国制造产品,那么当你把产品送进美国时,你要支付一笔关税,一笔非常高的关税。”

不过,他提出的关税远超所有人预期。国际贸易受到冲击,全球金融市场出现暴跌。面对市场动荡,特朗普在几天内又暂停了大部分关税计划。但此前举动已经损害了这个世界最大经济体的信誉。

华府的反复也让许多世界领导人感到困惑,不知道该站在哪一边。人们迫切想知道,特朗普的经济计划到底是什么?关税算盘究竟是为了什么?

BBC的“调查”(Inquiry)节目邀请了四位专家,深度分析特朗普的行动与布局,以及未来的方向。

“几乎整个全球秩序都被打乱了”

新关税先令外交领域陷入一片混乱。各国政府加快脚步,赶在7月的90天期限前与美国签订贸易协议。

艾米丽·基尔克里斯(Emily Kilcrease) 是华盛顿“新美国安全中心”(Center for A New American Security)的高级研究员兼能源、经济与安全计划主任。

她形容,特朗普的“美国优先”政策令美国与贸易伙伴的关系变得复杂,“几乎整个全球秩序都被打乱了。”

然而不只美国的贸易伙伴感到压迫,白宫本身也面对压力——法院随时可能介入,阻止总统的计划。

美国宪法明确规定,设定国际贸易政策是国会职责,而非总统权限。但特朗普称,美国的贸易失衡是一项“国家紧急状况”,要用总统行政令来设立关税。

“显然,他的行为正在突破甚至越过法律所允许他做事的权限。”基尔克里斯认为在未来一年,“法院对此很可能会有动作”。

至于国会方面,基尔克里斯也认为,国会的参与度会随着事态发展越来越明显。

“即便在共和党内部,也开始有人认为国会应该在制定政策上扮演更强的角色。因为很多人对政策方向感到忧心。即使他们支持总统的策略,但也对执行过程感到不安。”

“他们希望政策是可预测的,也希望能有发声的机会,确保自己选区内的企业和选民不会受到负面影响。”

但要推翻特朗普的关税政策并不容易。国会若要通过反对性法案,必须有共和党议员在参众两院倒戈。基尔克里斯指出,这样的动力可能来自国会之外。

因为关税影响的还有选民本身。特朗普曾说他在保护普通美国人,但这些人可能很快就要面对生活成本飙升的现实。

纽约一家杂货店的鸡蛋货架空空如也,店里还贴着限购标志,限制每位顾客购买一盒鸡蛋。

“他(特朗普)表明已预料短期内会有一些阵痛,但对他而言,长远看这一切都是值得的。”但基尔克里斯认为,当鸡蛋、日常生活用品的价格上升,贷款利率提高、买房变难,人们难以忽视切身变化。

她说,当众议院的代表收到越多选区内企业和选民的电话,反映政策的影响,由下而上的压力就一定会产生,促使特朗普对部分政策进行调整。

美国各州已经出现了大规模反特朗普的抗议活动,但到目前为止,特朗普的支持者在民调中遭遇的反对声音仍然不明显。那么究竟是怎样的叙事,至今仍吸引许多美国人?

特朗普“重新定位美国经济”

这或与特朗普身边的核心圈子有关。

卡拉·桑德斯(Carla Sands)是特朗普第一任期内的美国驻丹麦大使,也是他首次竞选总统时的顾问,非常熟悉特朗普的核心圈子。

“他身边有像凯文·哈塞特(Kevin Hassett)这样的经济顾问,还有财政部长史考特·班森特(Scott Bessent)。这两位都是理解特朗普主张、并且拥护这些理念的重要人物,他们两人风格截然不同。他身边还有其他真正的对华强硬派。”桑德斯说。

这些幕僚告诉特朗普,他需要重新定位美国的经济——他们认为美国过去几十年来制造业的空洞化,使国家陷入危险境地。

“我们长期因为糟糕的能源政策导致去工业化。我们鼓励企业将业务和制造业移到海外。我们这些西方国家说:‘我们的二氧化碳排放量很低。’但实际上,我们只是把生产转移到那些我们根本不在乎其碳排放的国家。”

桑德斯认为,一个国家必须自己生产东西,不能只做旅游业或知识型社会,然后期待自己能够安全无虞。

在她看来,关税有两个目标。第一,是为了让美国从服务型经济走出来,重新工业化。

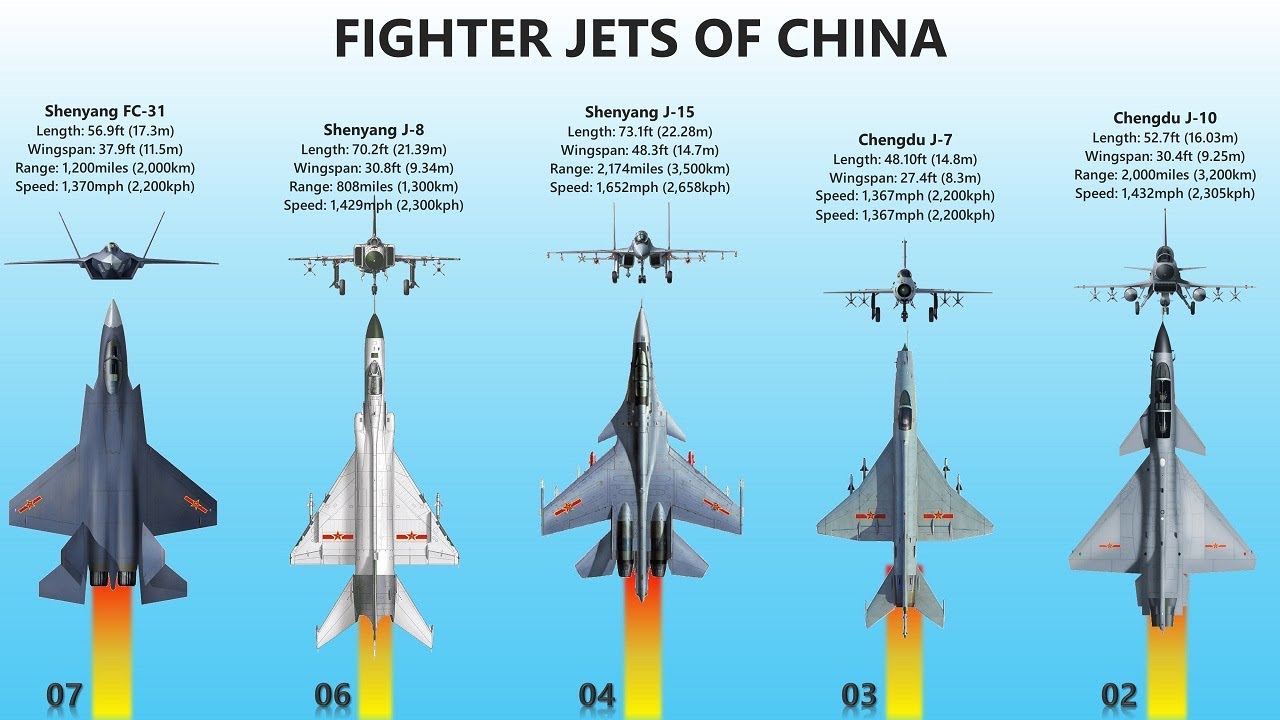

第二是对抗中国。“因为中国对西方、对我们的生活方式、对我们的自由构成了威胁。”桑德斯说。

目前,特朗普对中国征收的关税超过100%。这场角力有可能导致美中贸易完全停摆,让其他国家陷入两难:到底要站在哪一边?但与此同时,对美出口的国家也收到一个强烈讯号:华府对贸易失衡的容忍度已经到了尽头。

“过去我们就像是大家的‘老爸’,任人占便宜,但我们不在意。几乎每个国家对美国都有贸易顺差,几乎每个国家对我们的产品征收更高的关税,还有非关税壁垒。但特朗普的意思是,现在该为美国人民打造一个公平竞争的环境了,该讲互惠了。”

这一举动希望能把工作带回美国——桑德斯说,失业是美国许多社会问题的根源。

“我们有数百万男性对生活和生产失去热情。他们只是在家瘫在沙发上、吸毒、打电玩,享受着社会福利。特朗普想把他们带回劳动市场,找回自尊。”桑德斯认为,此举“非常有远见”。

一名工人在滨州市一家纺织服装生产企业工作

北京不让美国“得寸进尺”

但贸易是一件极其复杂的事,供应链经常跨越国界。美国的制造商可能仍然需要从其他国家进口原料或零件——这是一项庞大的挑战。

特朗普宣布关税措施后,各国政府急切跟美国谈判,只有一个国家没有打去电话:中国。

“中国绝不会允许世界上任何国家,包括美国,用最后通牒的方式对它颐指气使。中国认为,如果你退让一寸,特朗普和美国政府就会要求你让一尺。”中国全球化智库(Center for China and Globalization)副主任、苏州大学讲座教授高志凯(Victor Gao)说。

“所以你不能退让。因为一旦你向这种威吓和最后通牒低头,对方只会得寸进尺、不断索求。我认为中国坚信无论经济代价多大,都不会向霸凌行为妥协。”

在经济层面上,美国和中国谁损失更大尚有争论空间。但也许中国不太愿意与华府深入接触的另一个原因是:北京相信,美国选民最终会自己得出结论。

高志凯说,美国政府针对外国商品征收关税,其实是“由美国消费者买单”。“所以当我看到特朗普总统因为从关税中‘收了多少钱’而欣喜若狂时,我认为他要不是在误导自己,要不就是在误导美国人民。”

“他应该诚实地告诉美国人:是的,政府收了这笔钱,但这笔钱是美国人民付的。这实际上就是对美国人民征收的一种税。”

解决“看似无解的矛盾”:美元的地位和汇率

关税现时被延后实施。但新的全球秩序出现,地缘政治板块已经开始移动。

剑桥大学国王学院院长、《金融时报》专栏作家吉莲·邰蒂(Gillian Tett)说,随着中国影响力与实力上升,不少新兴市场国家开始转向东方,成为美国主导的国际秩序的替代选项。

“我们同时也看到一些传统上与美国结盟的国家——特别是欧盟,还有某种程度上的日本——对于特朗普政府对其征收关税感到震惊。他们有时悄悄地,有时公开地寻找更自给自足的方法,坦白说,他们也经常寻找替代方案。”

在改变关税决定之后,人们可以看到美国的目标正对准中国。许多世界领导人面对选边站的问题。但吉莲·邰蒂认为,特朗普的经济战略不只是重新调整全球货物流动那么简单。

“他们既把关税作为一种策略,也是一种武器,目的是推动整个全球体系的大重置。但他们也越来越多地把关税当作筹措收入、处理国家债务的方法。”

关税并不是针对盟友和敌人的单一震慑手段,而是更大拼图中的一块——特朗普希望解决美国庞大的债务。

目前,美国债务已膨胀至36兆(万亿)美元,不仅已经超过美国整体经济的规模。而其中很大部分——大约一兆美元——由中国购买。中国对美国出口大量商品,以美元收款。但北京用这些美元去购买美国国债,令美元走强。

“如果美元走强,就不利于出口,也难以与像中国这样的国家的低价商品竞争。因此,美国政府开始表示,我们希望保留美元作为储备货币,但我们不希望其价值过强,因为这会削弱我们自己的工业基础。”

“所以他们试图解决这个看似无解的矛盾:一方面希望美元继续支撑全球金融体系,另一方面又想让美元贬值。”吉莲·邰蒂说。

坊间也有很多传闻,指出存在一份特朗普计划核心的文件,名为《海湖庄园协议》。该文件据指欲以关税威胁持有美国国债的外国政府,逼使他们接受更低的投资回报率。

专家认为日本对美国的信任,正在以一种戏剧性的方式迅速消失。

这种举措对全球金融体系的影响难以说清。但可以肯定的是,这会震惊美国的贸易伙伴,加速他们制定对策。吉莲·邰蒂认为其中一项,是促进了欧洲领导人从军事国防到经济金融的合作。

“特朗普‘让美国再次伟大’运动最大的讽刺可能就是,他反而种下了欧洲‘让欧洲再次伟大’的种子......历史上我们看到,欧洲领导人总是需要一场危机,才能达成足够的共识并采取行动。而特朗普的激进行为,可能正创造出这样一场危机。”

至于中国,吉莲·邰蒂认为,中国因与东南亚及其他新兴市场国家建立更多联盟,可能变得更加强势,试图利用美国退居世界舞台后出现的权力真空,来扩展自己的影响力。

日本则陷入了两难处境。“它传统上是美国的亲密盟友,依然希望支持美国,也不希望中国主导亚洲,但同时,日本对美国的信任,正在以一种戏剧性的方式迅速消失。”她说。