Russia, no longer King of the North

Russia has long dreamed of becoming a superpower in the High North, thanks to its 24,000 km coastline on the Arctic Ocean.

The Northern Sea Route, which runs along Russia's Arctic coast, is considered the shortest available shipping path between Asia and Europe, some 30% to 40% shorter than routes that use the Suez Canal.

Leveraging its geography, Moscow requires all vessels sailing the route to be piloted by Russians, charges tolls and requires ships -- including warships -- to provide advance notice of their passage plans.

Many shipping companies prefer to use the Suez and Panama canals for this reason, even if they are lengthier journeys.

Many shipping companies prefer to use the Suez and Panama canals for this reason, even if they are lengthier journeys.

But the rapidly melting sea ice is opening shipping routes outside Russia's exclusive economic zone and closer to the North Pole itself. By 2065, the Arctic's navigability will increase so greatly that Russia's control over trade will weaken, according to a new study from Brown University in the U.S. state of Rhode Island.

Russia’s ambition to remain the Arctic superpower is propelling its all-out effort to guard its economic interests there with broad territorial claims over waterways and a continued military build-up in a region the United States often ignored, an expert on Arctic defense and security said Wednesday.

Troy Bouffard, director of the Arctic Security and Defense Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said President Vladimir Putin “really changed [Russia’s] approach to international development” and sees the Arctic playing a vital role in Moscow’s return as a great power.

At the same time, the warming waters in the Arctic are opening the Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage to longer seasons of shipping, making the waters factors for military and commercial planners in Washington, Moscow and Beijing.

But Russia has the biggest territorial claims in the Arctic, and it also sees the region as key to its future growth.

“Oil put Russia back on the map” as a nation of importance, said Bouffard, and energy sales remain critical to its economy.

“Right now, natural gas is the king,” particularly liquified natural gas from the Arctic because “that’s what’s marketable” and needed by China and Europe. He added that mining and fishing in the High North are complementing energy exploration and sales that help Moscow’s economy, despite sanctions levied on it after the seizure of Crimea in 2014 and continued backing of separatists in Ukraine.

To beef up its Arctic territorial claims over the Northern Sea Route – which is proving to be the more accessible route for trade between Asia and Europe – and restore its status as a military power, Bouffard Russia is spending 5 to 6 percent of its gross domestic product on defense.

He cited the July release of the Kremlin’s national security strategy as a statement that “they’re kind of back” when it comes to international affairs, demanding a voice and a seat at the table when it believes Moscow’s interests are at stake, as they are in the Arctic.

The report was released shortly after Moscow assumed the chairmanship of the eight-member Arctic Council. Although the council does not engage in military or security discussions, it is a forum for international cooperation on the environment, handling emergencies from search and rescue to providing disaster and humanitarian assistance and protecting the rights of the Arctic’s indigenous peoples.

In the document, Bouffard said the Russians “understand NATO is their biggest challenge” from the Arctic to the Baltic and Black seas.

When Putin and the Russian leadership look at the Arctic, they see seven other nations with territorial claims there that are either in NATO or partners like Finland and Sweden.

As a consequence of its vision of the Arctic as an economic engine for growth, Moscow “has done a better job of building out infrastructure,” from expanding its fleet of icebreakers to modernizing ports and ramping up military presence in specially-designed “Arctic Trefoils” military bases to back its claims over the Northern Sea Route, Bouffard and other speakers at the forum said.

The trefoils are designed to sustain military operations under severe Arctic weather conditions.

Bouffard added that one of Russia’s latest icebreakers, operating under the equivalent of its Coast Guard, is armed with missiles. It is “not going to escort tankers” along the Northern Sea Route.

Russia plans to expand its present fleet of more than 50 icebreakers to include “a flotilla” of nuclear-powered vessels by 2030 to keep the Northern Sea Route open for a longer sailing season.

This emphasis on defending what the Kremlin considers its own territory has translated into Russia building 10 dual use coastal stations along the Northern Sea Route. In addition, it has re-opened or built airfields backed up with S-400 air defense systems and modernized ports, often with Chinese investments to expedite liquefied natural gas exports. But the airfields also serve a military purpose, if needed.

Although Moscow hasn’t built artificial islands in the Arctic as Beijing has in the South China Sea, Bouffard said it beefed up its military presence on the waterway’s natural islands. “The islands offer great potential for sensors,” he added, as well as land for facilities to house air, land and naval forces.

Others in the forum suggested the Kremlin could be looking at installing undersea missile or torpedo pods to secure control of waterways in the High North. For the past two years, the Kremlin has been demanding non-Russian warships using the Northern Sea Route take aboard Russian pilots. The United States’ position on the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage is that both are straits, like that of Gibraltar and international waterways.

In assessing Russia’s land forces in the Arctic now, Bouffard said they “far outpace us now” in training under these conditions. In addition, these land forces are also rotated for training inside Russia’s borders and abroad. He included Syria as a training ground for Russian ground forces in developing new operational concepts for unmanned aerial systems and electronic warfare in a real world environment. He said “we’ll be there,” as the U.S. and NATO have stepped up their Arctic training to meet Russian challenges.

Answering a question, Bouffard said Russia’s Northern Fleet’s modernized ballistic missile submarine force has caused NATO to look again at the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom “gap” as a contested region in a potential conflict.

Earlier, he noted that after the collapse of the Soviet Union and before Putin became president, the only military force that was consistently funded was the Northern Fleet. Since then, the Murmansk-centered military commands of naval, air and land forces have been expanded and modernized.

For the Northern Fleet, this includes the addition of new attack and ballistic missile submarines and adoption of advanced undersea technologies that threaten the North Atlantic link between the U.S. and Canada and their NATO allies in a conflict.

“The security landscape [in the Arctic] is getting more difficult,” Ine Ericksen Soreide, Norway’s foreign minister, said earlier this year in Washington, reflecting on the Kremlin’s military modernization program and new strategy seeing itself as a great power.

据报告显示,截止到2020年,全球移民总数已达到了2.81亿人,占全球人口的3.6%,相当于每30个人中就有一位移民!

据报告显示,截止到2020年,全球移民总数已达到了2.81亿人,占全球人口的3.6%,相当于每30个人中就有一位移民!

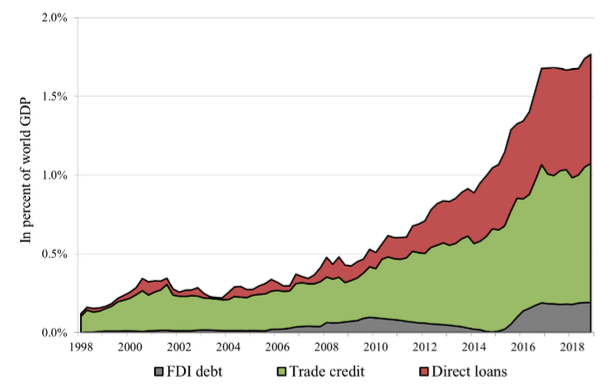

裴敏欣在《日经亚洲》发布评论提到,随着俄罗斯入侵乌克兰,高通膨、利率上升以及美欧经济衰退迫在眉睫,许多贫穷国家正面临着自2008年全球金融危机以来最严重的经济困境。这些穷国过去15年中,获得数千亿美元的贷款,如今面临资本外逃、粮食短缺,低收入国家的政府发现越来越难以偿还中共贷款,而且有些国家积欠中共的债务比台面上的还要多,估计中共对发展中国家提供的未批露贷款,至少占这些国家GDP的15%。

裴敏欣在《日经亚洲》发布评论提到,随着俄罗斯入侵乌克兰,高通膨、利率上升以及美欧经济衰退迫在眉睫,许多贫穷国家正面临着自2008年全球金融危机以来最严重的经济困境。这些穷国过去15年中,获得数千亿美元的贷款,如今面临资本外逃、粮食短缺,低收入国家的政府发现越来越难以偿还中共贷款,而且有些国家积欠中共的债务比台面上的还要多,估计中共对发展中国家提供的未批露贷款,至少占这些国家GDP的15%。 中共身为这些穷国的最大单一债主,且近三分之二的贷款用于基础建设。在经济低迷时期,收费公路、港口和发电厂等已建成的基础设施项目,将因交通和电力消耗减少冲击营收,难以产生足以偿还中共贷款的收入。其次,由于中共的贷款通常以资源产生的收入为抵押,在经济衰退期间违约风险会显著上升,因为需求下降通常会压低大宗商品价格,目前仅石油等能源除外,这些因素也会令偿还债务所需的收入减少。

中共身为这些穷国的最大单一债主,且近三分之二的贷款用于基础建设。在经济低迷时期,收费公路、港口和发电厂等已建成的基础设施项目,将因交通和电力消耗减少冲击营收,难以产生足以偿还中共贷款的收入。其次,由于中共的贷款通常以资源产生的收入为抵押,在经济衰退期间违约风险会显著上升,因为需求下降通常会压低大宗商品价格,目前仅石油等能源除外,这些因素也会令偿还债务所需的收入减少。

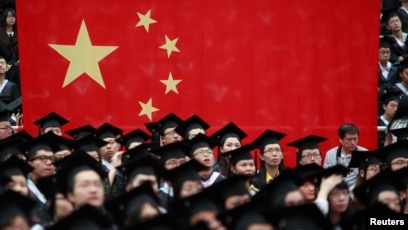

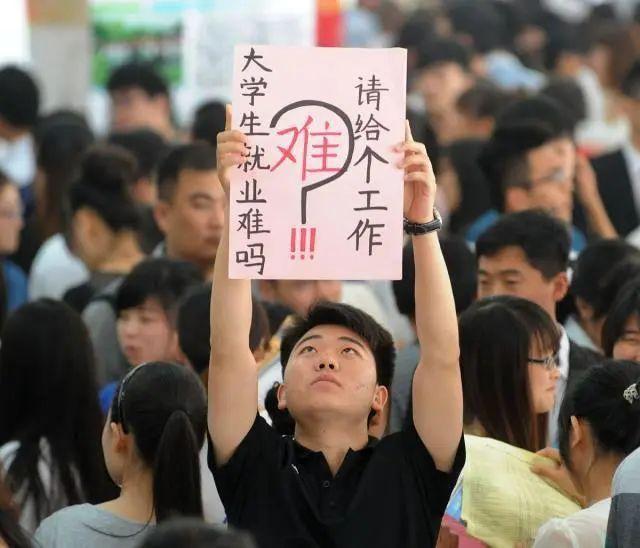

由于房地产市场低迷、地缘政治忧虑和对科技、教育和其他行业的监管打击本已经放缓的中国经济,又受到新冠防疫限制措施的打击。今年的毕业生面对的是数十年来最糟糕的就业市场。根据6月份发布的官方统计数字,目前中国18至24岁人群失业率达到18.4%,是整体失业率的三倍之多。

由于房地产市场低迷、地缘政治忧虑和对科技、教育和其他行业的监管打击本已经放缓的中国经济,又受到新冠防疫限制措施的打击。今年的毕业生面对的是数十年来最糟糕的就业市场。根据6月份发布的官方统计数字,目前中国18至24岁人群失业率达到18.4%,是整体失业率的三倍之多。 一场监管风暴使包括腾讯和阿裡巴巴在内的许多中国的科技巨头进行大规模裁员。路透社援引多位科技业内人士说,今年以来,该行业有数万人失去了工作。据上海的人才管理咨询公司诺姆四达(NormStar)今年4月发布的一份报告,中国大约

10 家最大的科技公司之间的裁员人数各不相同,但平均约为 10%。

一场监管风暴使包括腾讯和阿裡巴巴在内的许多中国的科技巨头进行大规模裁员。路透社援引多位科技业内人士说,今年以来,该行业有数万人失去了工作。据上海的人才管理咨询公司诺姆四达(NormStar)今年4月发布的一份报告,中国大约

10 家最大的科技公司之间的裁员人数各不相同,但平均约为 10%。